Reading a handwritten manuscript is very exciting: you never know what is just over the next page.

Lately I have been reading through the manuscripts held by the National Library of Scotland and alighted upon something rather unusual. It is a manuscript from a bakery, with appropriately large batch quantities. It is a fascinating peek into the variety of bakes and extras that formed the day to day offerings of a Georgian bakery.

The manuscript has been dated to 1827, which puts it slap-bang in the middle of the reign of George IV, but other than that, there appears to be no other identifying information. Now this might be looked upon as more than a little frustrating, however, being much more of a glass-half-full person, I usually see it as an opportunity for sleuthing, and seeing whether or not I can glean any more information from the pages within.

Firstly, I think the date is very well chosen, and I’m sure the Library of Scotland is nothing short of THRILLED at my approbation. This I deduced from the raising agents used in the recipes, which call either for yeast or volatile salts. Volatile salts are the precursor to baking powder, which was only a mere fifteen years away from being invented.

Another piece of information I noted gave me reason to believe that there may well be a Scottish link, aside from where the manuscript is currently held, is the use of ‘carvey’ for caraway seeds. In the 18th century, the word was in much greater use throughout the British Isles, but in the 19th century, it was retained mostly in Scotland. The one thing holding me back from declaring this a definite is the Englishness of the other recipes: Abernathy biscuits, Bath cakes and buns, Weymouth biscuits, Stratford cakes, Norwish biscuits, Isle of Wight cracknels…

The recipes themselves cover a wide range of items: biscuits, cakes, buns, jams and jellies, sweeties, custards, bread, muffins and cakes. I love this manuscript for its sheer uniqueness. I have a small but favourite collection of commercial baking books dating from around the turn of the 20th century, but I’ve not come across any other handwritten recipes of catering size quantities of this early age. Browsing for something for Easter, I came across this recipe for Buns for Shops or Cross Buns. Perfect!

But it came at a price. And the price was the spelling.

Oh my dears, the spelling.

I fully appreciate that spelling from 200 years ago is going to be a little quirky, but this… This is on a whole new level.

In case your cursive reading skills are a little rusty, allow me to transcribe the recipe for you, with the original spelling.

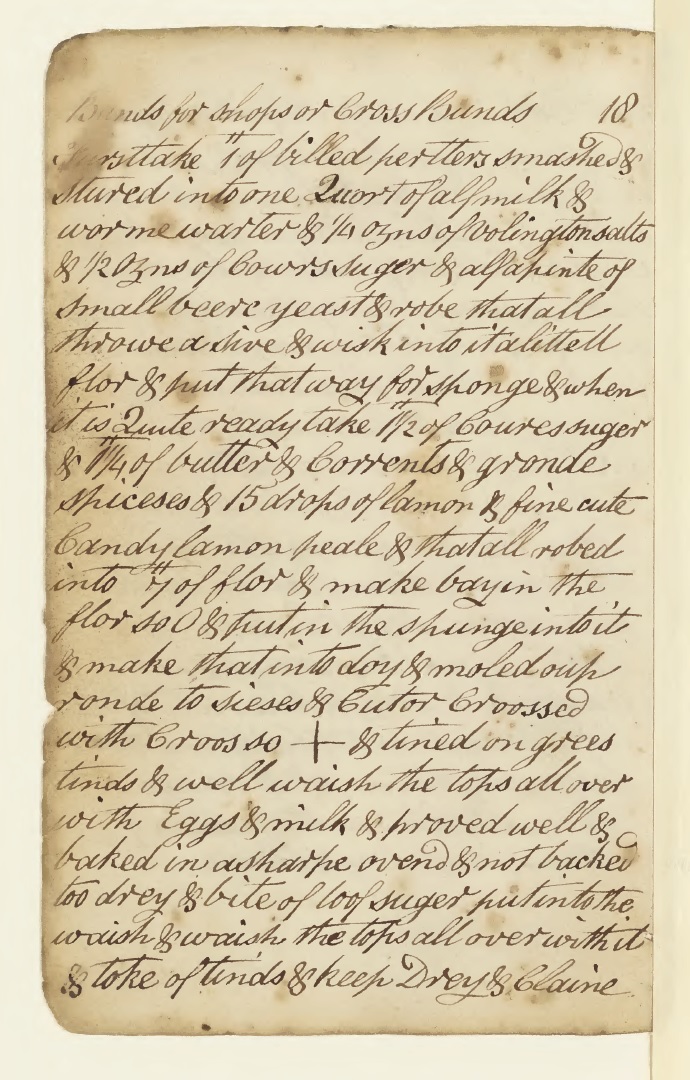

Bunds for shops or Cross Bunds

Fursttake 1″ of billed pertters smashed & stured into one Quort of alfmilk & worme warter & 1/4 ozns of volington salts & 1/2 ozns of Cours suger & alfa pinte of small beere yeast & robe that all throwe a sive & wisk into it a littell flor & put that way for sponge & when it is Quite ready take 1 1/2″ of coures suger & 1 1/4″ of butter & Corrents & gronde spiceses & 15 drops of lamon & fine cute Candy lamon pale & that all robed into 7″ of flor & make bayin the flor so O & pit in the spunge into it & make that into doy & moled oup ronde to sieses & Cut or Croossed with Croos so + & tined on grees tinds & well waish the tops all over with Eggs & milk & proved well & baked in a sharpe ovend & not backed too drey & bite of loaf suger put into the waish & waish the tops all over with it & toke of tinds & keep Drey & Claine.

The modern translation is as follows:

Buns for shops or Cross Buns

First take 1lb of boiled potatoes mashed & stirred into one Quart of half milk & warm water & ¼ oz of volatile salts & ½ oz of Coarse sugar & half a pint of small beer yeast & rub that all through a sieve & whisk into it a little flour & put that away for sponge & when it is Quite ready take 1½lb of coarse sugar & 1¼lb of butter & Currants & ground spices & 15 drops of lemon & fine cut Candied lemon peel & that all rubbed into 7lb of flour & make a bay in the flour so – O – & put the sponge into it & make that into dough & mould it up round to size & Cut or Cross with a Cross so + & put them on greased tins & well wash the tops all over with Eggs & milk & prove well & bake in a sharp oven & don’t bake too dry & add a bit of loaf sugar into the wash & wash the tops all over with it & take them off the tins & keep them Dry & Clean.

Yes, that first ingredient is boiled potatoes, and I will freely admit it took me a good half hour of pondering and saying the phrase out loud to myself in a frankly embarrassing number of accents in order to try and work out what it might be. Adding mashed, boiled potatoes to a bread recipe helps keep the resulting buns from drying out too quickly and keeps them pleasantly chewy. ‘Volington Salts’ makes me chuckle, because it sounds like the name of a Georgian Dandy.

The travails of translating the handwriting aside, there are two aspects of this recipe that I love. Firstly, it is the unusual (to modern palates) combination of spicings and flavourings. The recipe calls for both lemon essence and candied lemon peel as well as ‘mixed spices’. I’ve also made some biscuits from this book which called for cinnamon and lemon, and maybe its because this combination seemed so unusual to my 21st century palate, but to me they tasted Georgian. The ‘mixed spices’ gives you carte blanch to use whatever combination you like, but I’m going to recommend cinnamon and nutmeg, which were a popular combination for decades in the 17th and 18th centuries. The lemon flavouring, for some reason, I found problematic: liquid flavouring seemed to fade when baked, so I tried using finely grated fresh lemon zest, which also didn’t have quite the punch I was looking for. Perhaps a combination of the two will give the lemon burst I think these might need – but if we hang around for me to trial that, we’d miss Easter, so onwards!

Georgian Cross Buns

This is a 1/7th scale of the original recipe, and will make 18 x 60g buns. If this is a bit much, halve the recipe and divide the dough into 8 buns. Make a sponge if you feel inclined, but I went for mixing all together at once.

70g cooked mashed potatoes

100ml milk

100ml water

450g flour

7g sachet of fast action yeast

100g caster sugar

80g butter

1tsp ground cinnamon

1tsp ground nutmeg

1 tsp lemon flavouring and/or zest of 1 lemon

60g fine sliced candied lemon peel

125g currants

For the glaze

1 large egg

1/2 an eggshell of milk

2tbs caster sugar

- Heat the milk and water to blood temperature.

- Add the cooked potato and whisk together – a stick whisk works well to make the mixture smooth.

- Put the flour, yeast, sugar, butter, spices and lemon flavouring(s) into a food processor and blitz until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs.

- Put the liquid mixture into a mixing bowl and add the dry mixture on top.

- Knead for 10 minutes. Don’t be tempted to add more liquid – there’s moisture in the butter and the working of the dough will bring that out and make a dough that ‘cleans the bowl’.

- When the dough has come together and is smooth and elastic, mix in the currants and lemon peel.

- Cover the bowl with plastic and set aside in a warm place to double in size. If your kitchen is on the cool side, use your oven: Turn the heat to 170°C/150°C Fan for TWO MINUTES ONLY, switch off, and place your bowl inside. Due to the enrichments of butter and sugar, this may take longer than normal, probably closer to 90 minutes.

- Tip out the risen dough and gently deflate by pressing with the hands.

- Divide your dough by weight: 60g makes a decent-sized bun, but go larger if you prefer a more substantial bun.

- Roll the dough into a smooth ball, press flat with the palm of your hand, then arrange on a parchment-lined baking sheet at least 3cm apart.

- Cover lightly with plastic and allow to rise a second time (30-45 minutes).

- Heat the oven to 180°C, 160°C Fan.

- When the buns are sufficiently risen, cut a cross into them. I find pressing (not rolling) a pizza wheel down into the buns is an ideal tool for this: it marks a deep cross, but doesn’t cut through the edges of the bun and cause them to split during baking. Alternatively, use the flat end of a spatula.

- Whisk the egg and milk together, and glaze the buns by brushing the mixture over them using a pastry brush.

- Bake for 15-20 minutes, depending on size. For the smaller 60g buns 15 minutes is fine. If your buns are larger, then leave them for 20 minutes. Turn the baking sheet around halfway though.

- While the buns are baking, add 2tbs caster sugar to the remaining bun wash and stir to dissolve.

- When the buns are baked and golden brown, remove from the oven and place the baking sheet on a rack. Brush the hot buns over with the sweetened bun wash. The heat of the buns will set the sweetened glaze, and your cross buns will cool with a lovely shine.

- Remove the buns from the baking sheet when cool and store in an airtight container.

- Serving suggestion: Delicious when freshly baked. When cooled, cut in half and toast both sides. Serve warm with butter and a sharp cheddar cheese.

They sound great. But no salt?

LikeLike

Hi Martin,

No, no salt in the original recipe. That may be due to any one of a number of reasons: it might be a ‘sin of omission’, either because the author forgot or because it’s such an obvious element, the author doesn’t include it because ‘everyone knows’ you add salt to dough.

It also might be because the salt is in the butter, which in the days before refrigeration was heavily salted and packed into barrels, then rinsed, or not, when required.

I didn’t find the buns lacking, but then I ate them with salted butter and strong cheddar, which also has salt.

My suggestion is to try the recipe as is, and if you think it needs it, use salt butter and/or cheese, and make a note to add salt for the next time.

Hope this helps!

M-A 😀

LikeLike