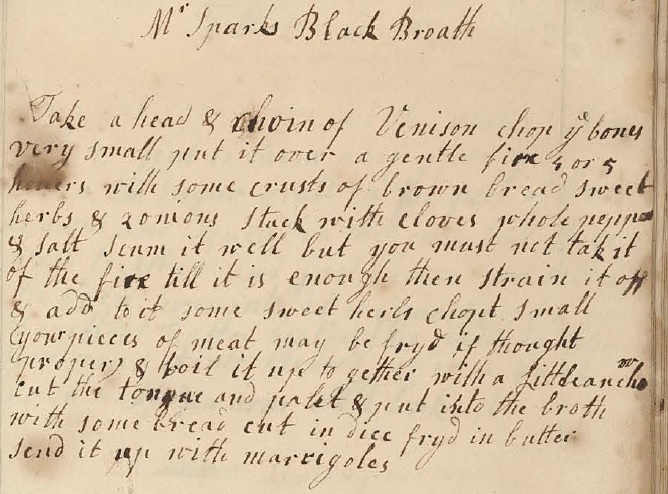

I have no idea who Mr Sparks was, but he obviously made an impression on at least one of the many ladies through whose hands one particular manuscript¹ passed, for there are no fewer than nine of his recipes included over the course of ten pages.

I have been unable to find any printed cookery book with a Mr Sparks as author, so must assume that these recipes were copied from one handwritten source into another as a result of having tasted the dishes in question. I almost have more confidence in a handwritten recipe with a name attached that is otherwise untraceable, because it hints at genuine originality: someone created it, someone ate it, that someone liked it so much, they asked for the recipe.

This black broth is made with venison. Venison is beautifully lean meat, which also means that it can be prone to toughness on the less prime cuts such as shoulder, or the ‘helpfully’ diced meat (that gives no hint as to which part of the animal it came from) available in packs in the supermarket.

Long, slow poaching in a flavoursome broth makes for fall-apart tender meat, perfect for a warming winter soup. This recipe uses a method gleaned from old manuscripts that is the opposite of what we do today, namely frying the meat after it has been cooked. I’ve used it with ragoos and fricassees and have been delighted with the added richness it gives both to the flavour of the meat and to the dish as a whole. The butter might seem extravagant, but it is a sumptuous

complement to the leanness of the venison.

A slow-cooker is ideal for this largely set-it-and-forget-it hearty soup, but you can also cook it on the stove top on a very low heat, or covered in the oven at 140°C/120°C fan/gas 1.

Black Broth

1kg venison shoulder, in one piece if possible, otherwise cut into large cubes.

3 slices wholemeal bread

3 onions

9 cloves

1 bunch parsley

1 bunch mixed herbs

1tbs peppercorns

1tsp salt

1.5 litres beef stock

50g unsalted butter

3-4tbs chopped, mixed herbs

gravy browning (optional)

2-3 slices of white bread, crusts removed, cut into 1cm cubes

marigold petals to garnish

- Toast the bread as dark as possible without turning black.

- Peel the onions and stick 3 cloves into each one.

- Add all of the ingredients down to the stock to the slow cooker and cook on low for 8 hours.

- Remove the meat from the cooking liquid and trim all fat, skin and connective tissue. Cut into suitably-sized pieces if not already cubed.

- Strain the cooking liquid and discard the solids. Remove all fat from the broth, either with a separator jug or by chilling the liquid in the fridge and allowing the fat to solidify on top, then lifting off. Taste and decide if the broth requires any embellishment. You can improve the flavour of the broth, if necessary, with various flavouring sauces such as, but not limited to, mushroom ketchup, walnut ketchup, anchovy essence, Henderson’s Relish, Worcestershire Sauce, Marmite, Bovril, soy sauce.

- Melt the butter in a large pan and add the pieces of cooked venison.

- Braise the meat over a medium-low heat, turning often but carefully, to avoid breaking it apart further, until the meat is richly browned.

- Return the meat to the broth and heat through. Add the chopped herbs and taste to check the seasoning. Add pepper, salt and more of the flavourings as required. If you’d like your broth darker, use a drop or two of gravy browning.

- Add the cubed bread to the remaining butter and toss over medium heat until crisped and browned.

- Serve sippets (for that is what you have just made) and marigold petals (if available) sprinkled into the broth.

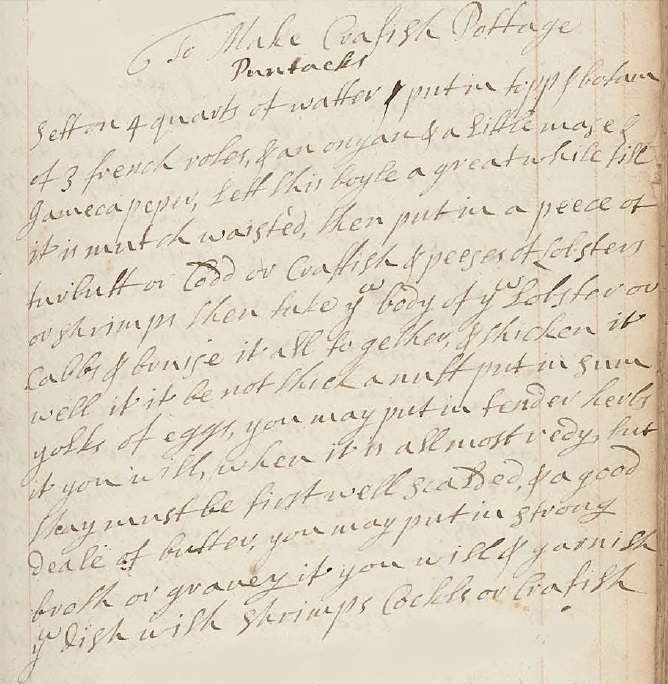

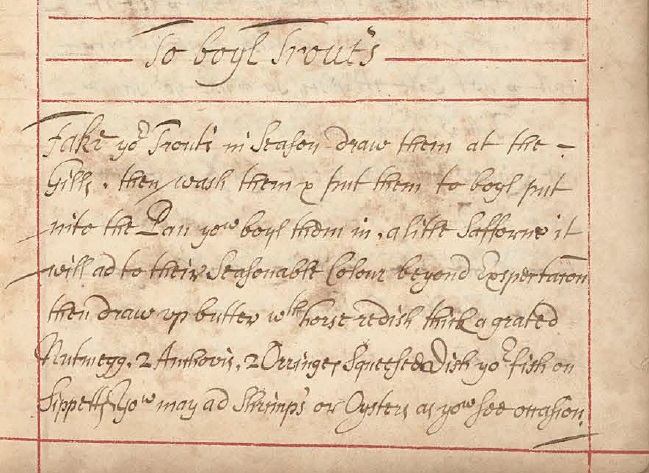

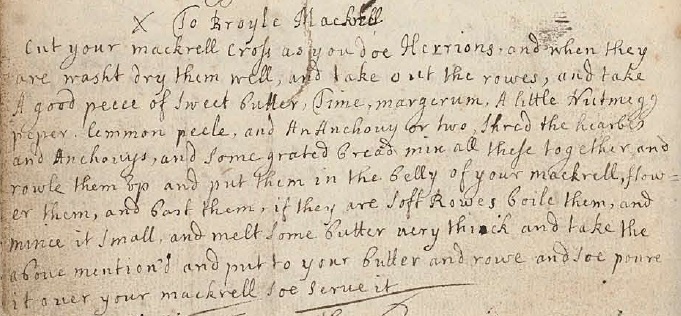

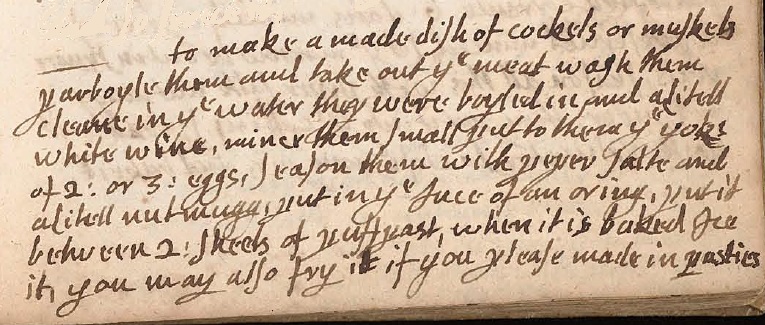

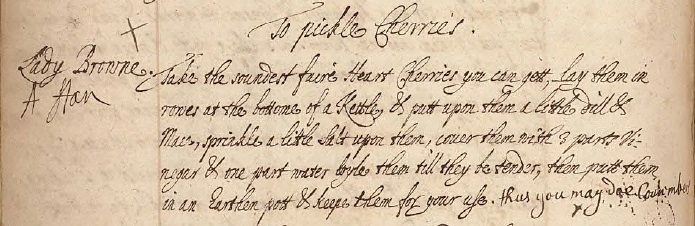

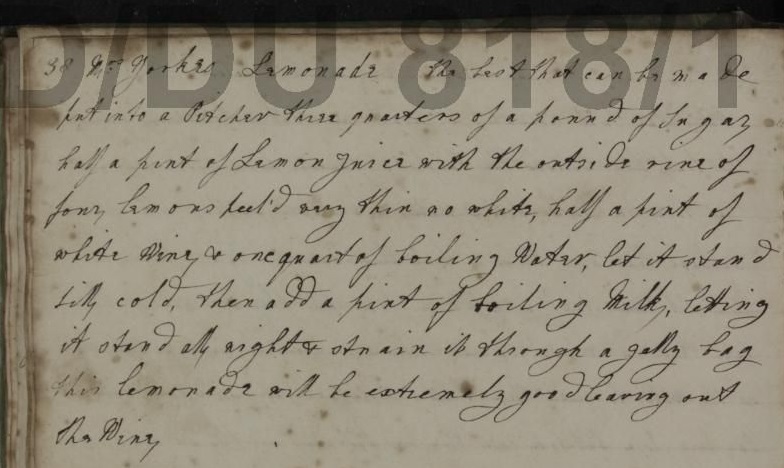

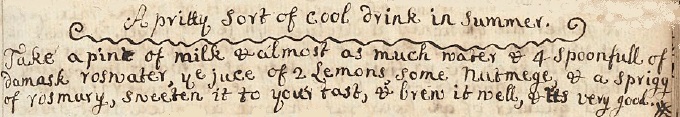

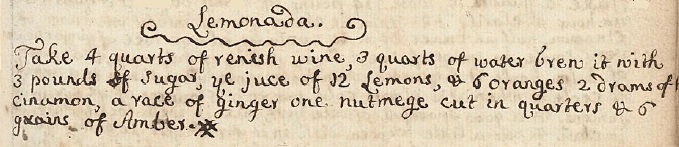

¹ MS7851, Wellcome Library Collection. Various marks of ownership are written in the book, in a number of hands. ‘Elizabeth Browne 1697’, ‘Penelope Humphreys’, ‘Sarah Studman’, ‘D Milward’ and ‘Mary Dawes Jan 18 1791’.