This recipe is such a delight. So simple, so eye-catching, and almost 400 years old.

It comes from one of my favourite manuscripts at The Wellcome Collection. Now I’ll freely admit I am very fickle with my favouritism, and I have been reminded this week of just how special this manuscript is, mainly due to a completely different manuscript I’ve been working on. I’m not going to name and shame it, but my dears… The handwriting. The spelling. Lets just say, I was sorely tested.

THIS manuscript, however, is an absolute delight. Straddling the 17th and 18th centuries, the handwriting is surprisingly modern: neat, well punctuated, with a pleasing layout, it is a joy to read, and I regularly have to remind myself just how old it actually is.

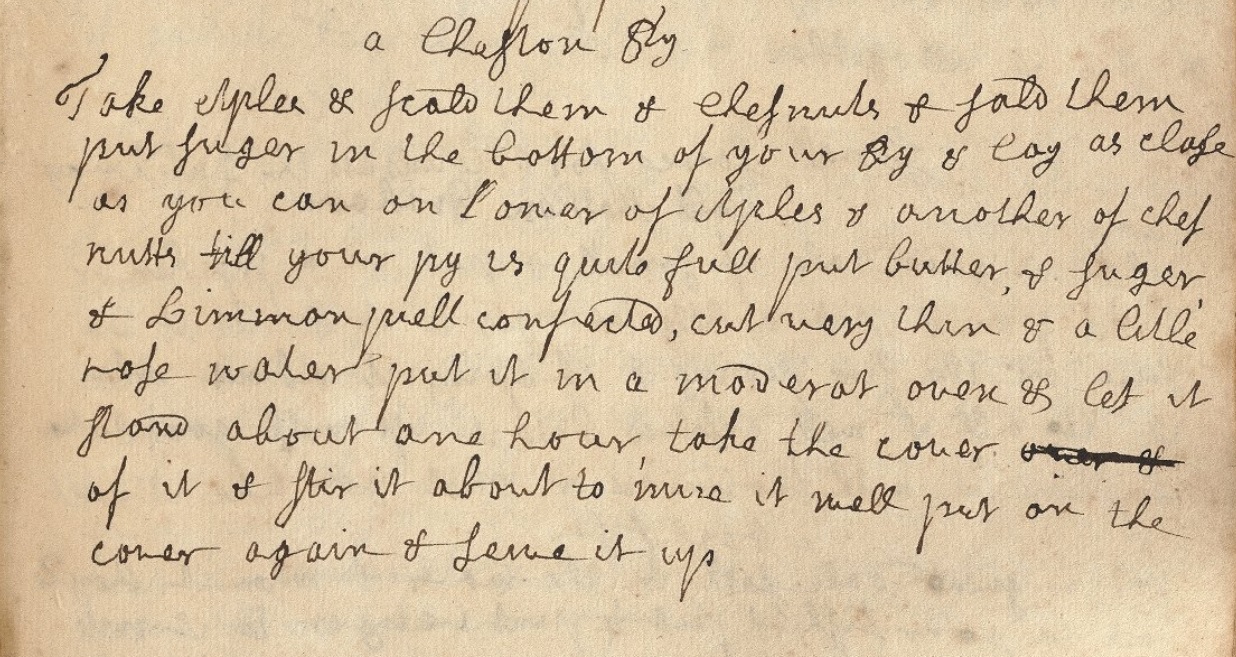

The method used to ‘carnival’ fruit is to dip it into a clear caramel. Although I have used several different fruits in the top image, the fruit recommended in the recipe is ‘a Cheney Orange’ (China Orange), aka an eating orange (as opposed to a Seville bitter orange). Since oranges are in season during the winter months, I believe this is perfect dish to serve up during the festive season. Nowadays we have the luxury of fruit out of season, which can make for a very colourful display, however, some fruit are more suited than others. Very moist, juicy fruit such as strawberries and cherries (not pictured) will only last 2 hours before the shiny caramel coating starts to break down. Other fresh fruits such as grapes, physalis, blueberries, nuts and even dried fruit such as apricots will last 3 hours before starting to become sticky. Whilst you can do orange segments, I feel that against the scale of the other fruit, they’re a bit big, and that small orange segments (satsuma, mandarin, clementine and the like) would be more suitable.

I have changed very little in this recipe: I’ve added some weights and measures, to help with getting the sugar to the correct stage and added a little liquid glucose to keep the caramel from crystallizing. I tried several times to go ‘old school’ with just sugar and water, but the caramel always crystallized too quickly to get more than just a few pieces dipped. Perhaps they used honey to help them out back then?

When choosing your fruits and nuts, it is important to consider how they are going to taste with the caramel. If you have a sweet tooth, then it gives you free rein to pick and choose almost anything. Personally, I would recommend choosing fruit that is slightly sharp, just to prevent an overload of sugar. The fruit also needs to be dry, so this rules out any fruit so large it needs to be sliced.

Choose your favourites from: green/red/black grapes, cherries, strawberries, raspberries, strings of redcurrants, blueberries, blackberries, physalis, dried apricots, walnuts, hazelnuts, pecans, almonds. If you have the patience to put individual pomegranate seeds on cocktail sticks and dip them, I think they would be delightful in both appearance and flavour.

The greatest amount of time for this recipe will involve preparing the fruits and nuts.

- You can utilise the stalks on cherries and redcurrants, the papery coverings on physalis and the green stalks on strawberries to hold as you dip them in the caramel.

- Most other fruits and nuts can be pierced with a wooden cocktail stick to prevent getting boiling caramel on your fingertips.

- The recipe recommends using a thread to dip orange segments, and I must confess to not having tried this method. I opted instead to use the cocktail stick. If you can pierce the skin and avoid bursting any of the juice sacs inside, you’re onto a real winner.

To Carnival Fruit

For the caramel

400g granulated sugar

125ml water

60ml/4tbs/¼ cup glucose.

a selection of fresh fruits, berries and nuts

wooden cocktail sticks for dipping

a silicone mat or baking parchment

a sugar thermometer

- Put the sugars and water into a small saucepan and set aside to begin dissolving while you prepare the fruit for dipping.

- Use the wooden cocktail sticks to skewer the fruit and lay them neatly on a board or plate. If you’re using small orange segments, remove all the white pith. If you accidentally tear the skin of a segment, eat it – the juice will compromise the caramel.

- Line a baking sheet with the silicone mat or baking parchment. This is for laying the dipped fruits on to cool. Although the dipping is straightforward, you will need to work fairly briskly in order to get all the fruit dipped before the caramel cools. If you can keep the pan on a very low heat while you dip your fruit, then this won’t be much of a problem. However, the heat will continue to cook the caramel, and it will become darker the longer it remains on the heat.

- Arrange the prepared fruit and baking sheet so that they are easily to hand when the caramel is ready.

- Heat the pan with the sugars in over a low heat until the granulated sugar has dissolved.

- Increase the heat and cook until the syrup registers 150°C on a sugar thermometer. The syrup will be bubbling vigorously over the whole surface of the liquid.

- Remove from the heat (or turn the heat down to the minimum, your choice), and begin dipping your fruits and nuts.

- Tilt the pan so that the syrup is deep, and then one at a time, dip your fruit fully into the caramel and set on the silicone mat/parchment to cool. For fruit not on wooden sticks, be sure to keep your fingers well away from the caramel when dipping, as the caramel will burn, and stick to your skin and continue to burn, if it comes into contact.

- The caramel needs only a minute or two to set, and then all that remains is to arrange it on your serving dish and serve. I went for a wooden board, as it’s plainness and natural material made for a great contrast against all the brightly coloured, shiny carnival fruit. To remove the wooden sticks, roll them between your thumb and forefinger – this will provide enough pressure to break the caramel surrounding them, thus making it easy to remove them.