Something a little different for you this week, dear Reader, and something of a surprise, perhaps.

These are Nantakies: Indian shortbread biscuits that are still enjoyed today, mainly at Christmastime.

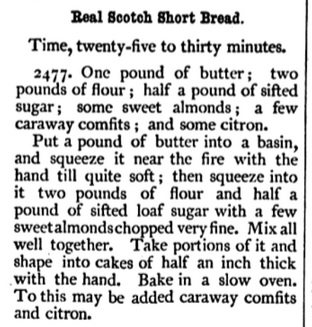

This particular recipe comes from a book printed in 1887 in Bombay (Mumbai) at the height of the British rule in India. It is one of many Indian cookery books in English that I have collected over the years and is freely available to download at The Internet Archive.

What first drew me to this shortbread recipe was the small number of ingredients when compared to modern recipes. Also, following on from my earlier shortbread investigations, I was curious to know how using 100% ‘rolong’ (semolina) as the flour ingredient would affect the taste and texture.

Initially, testing this recipe went poorly, because I used coarse semolina. Switching to finely ground semolina (found in my local orange supermarket under the brand name Natco) was a great improvement. It was still too sweet for my tastes, so I tinkered a little with the ratios and switched out regular butter for more appropriate clarified ghee.

In the UK, ghee can be found in supermarkets and smaller shops in distinctive green and gold tins. Once opened, they don’t require refrigeration and can be stored in a drawer/cupboard. However, I must impress upon you that not all tins of ghee are the same. The very best brand, in my humble opinion, is East End.

Opening this brand especially, releases an almost perfumed aroma that immediately sends you to a more exotic and fragrant place. I have not had the same experience with other tins of ghee – purchase them at your peril!

The result of the tweaks and changes made for a wonderfully aromatic and decadent shortbread bite, needing no further flavouring. However, if you’d like to add a hint of cardamom or rosewater, I think it would be a delicious variation. The golden colour from the ghee remained during baking in the cool oven and I have added a gold dragee to the top of each one as an exotic but restrained decoration.

You will have noticed that there are two shades of biscuit in the above photograph. Spurred on by my success with the tweaked original, I also made a gluten-free version using ground rice instead of semolina, and accented the biscuits with a silver dragee. I used up most of my ground rice in doing so and when I went to buy more I was disappointed to find that my local shops no-longer stock ground rice as a matter of course: perhaps it’s viewed as old-fashioned. I would have thought it would be readily available, given its usefulness in gluten-free baking, but there are numerous shops online that stock it, so all it requires is a little forward planning.

I wanted small, neat biscuits and having persevered with hand rolling various sizes, I eventually found the perfect ‘mould’ in my tablespoon measuring spoon. It was a little fiddly to form the biscuits one by one, but well worth it in the end result.

Nankaties – 1887, Mumbai

Makes 12-20 biscuits, depending on size.

150g finely-ground semolina or ground rice if gluten-free

75g ghee

35g icing sugar

gold/silver dragees for decoration

- Heat the oven to 150°C, 130°C Fan if baking the biscuits immediately. Otherwise, heat the oven just before removing the chilled biscuits from the fridge.

- Put the ingredients into a food processor and blitz until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs. It will have a texture of damp sand, and will hold together when pressed.

- Tip out the mixture and shape your biscuits – either by hand rolling or by pressing it into a mould. If you choose the measuring tablespoon method mentioned above, I found it useful to use some plastic wrap/cling film to line the spoon, which made it very easy to remove the moulded biscuits without damaging them. Be sure to pack the mixture firmly in order for it to keep its shape during baking.

- Arrange your biscuits on a baking sheet lined with parchment or a silpat mat.

- Add the dragee decoration if using.

- You can chill the biscuits in the fridge for 30 minutes before baking, if liked. It can help retain a neat shape, although I should point out that the biscuits in the photo above were not chilled before baking. If you want especially crisp edges to your biscuits, you can always neaten them once cold with a microblade grater.

- Bake for 30-40 minutes until crisp. The colour won’t really change, due to the low temperature.

- WARNING: the biscuits will be extremely delicate when hot. Leave them to cool on the baking sheet/tin until completely cold before moving them.

- Store in an airtight tin.