We don’t eat buns as frequently as we used to, and I think it is a great shame, because buns are synonymous with fun!

I spend a lot of time pondering different recipes, and one thing that causes much musing is the way recipes evolve in the UK, compared to, say, France.

French recipes tend to be rather rigid and proscribed. Definitions of what constitutes those two most recognisable of French baked goods – the croissant and the baguette – have been firmly established, almost set in stone. A croissant is a croissant, a baguette de tradition is a baguette de tradition, – there are rules, there is order, and there is never, ever, deviation. You want to tweak a recipe a little? Then you have to give it a new name. The French have no truck with ‘croissant-ish’ or ‘baguette de tradition adjacent.’ No messing about with rules that have been decided decades, even centuries, ago. Absolument pas!

In contrast, British recipes are a lot more open to interpretation. On the Books and Writing page of this website you will find, amongst other things, a paper I wrote on Pikelets, and how, over the centuries, the word has been used to describe different recipes for arguably quite different items. Also a paper on Summer Pudding, which has undergone its own transformation during its long and illustrious history.

Having given the matter a great deal of thought, I’m pretty comfortable with viewing recipes, especially British ones, as having a timeline. Some are long, some short, but throughout which adapts and changes with tastes and fashions. To illustrate this, in Great British Bakes, I included multiple recipes for Shrewsbury Cakes, an all but forgotten English shortbread that has a history spanning centuries. Others, such as the less-successful Crimson Biscuits (be honest – have YOU ever heard of them?) in Ann Peckham’s 1767 book, have timelines of alarming brevity. An added feature (frustration) with British recipes is that they might go by a number of different names, according to region, or indeed the one name may refer to numerous different dishes.

And so, after WAY too much preamble, we come to Bath Buns, whose history stretches back into the 1600s, and might be a genuine contender for Britain’s Oldest Bun, much to the probable dismay of fans of Sally Luns and Chelsea Buns, very much the Johnny-Come-Latelies of the eighteenth century pastry scene. The glitterati of Bath were happily taking the waters and chomping on this style of bun for the best part of a century before Dr Oliver invented his biscuit in an effort to improve the health of The Ton.

The Bath Bun of the late 17th century is rather different to the buns we might find in bakeries and tea shops today. The early Bath Buns were sweetened and flavoured with caraway comfits: seeds enclosed in numerous layers of sugar and enjoyed as sweetmeats and digestives. Today, a classic Bath Bun should retain the image of these candied seeds by being topped with pearled or candied sugar, which retains its colour and shape during baking, giving them a very distinct appearance. The time and effort required to create seeded comfits is considerable, and it is unsurprising to learn that they are no longer made. In imitation, I have found that using pearled/candied sugar and a sprinkling of unadorned seeds provides the sweetness, flavour and crunch of these forgotten sweetmeats.

The original Bath Buns were also incredibly rich with butter. Looking at recipes throughout the century, the most popular ratios ranged from an almost paltry one third of the weight of flour in butter, up to croissant-exceeding levels of 1.5 times the weight of flour in butter. Add in, as in the recipe below, a couple of pounds of caraway comfits, and these buns are probably a major cause of the gentry having to ‘take the waters’.

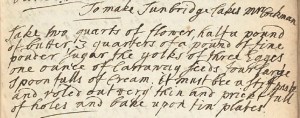

The first recipe below, the earliest I could find, is from an old manuscript dated to ‘late 17th century’ and has an equal weight of flour and butter. I scaled the recipe down, but there was still an alarming quantity of butter in not much dough. I broke my own rule too, in the baking, and did not bake it as written. Partly because I suspect that there is an error in the transcribing the original ingredients, and partly because I just couldn’t bring myself to put the full complement of sugar into the dough. I settled for half, and even that was a challenge – the buns were practically crystallized!

With all the eggs and butter and sugar the dough is incredibly soft – too soft to knead – and is practically spooned onto baking trays – something which later recipes mention frequently. The modern Bath Bun traditionally should have a rather rough appearance, and shuns the round perfection of Sally Luns or the even sugared, square edges of the Chelsea Buns. Due to all this richness, the dough can take a long time to rise and the finished texture is cake-like rather than bready, crunchy with the sugar crystals and with the unusual (to our modern palates) and distinct flavour and aroma of caraway.

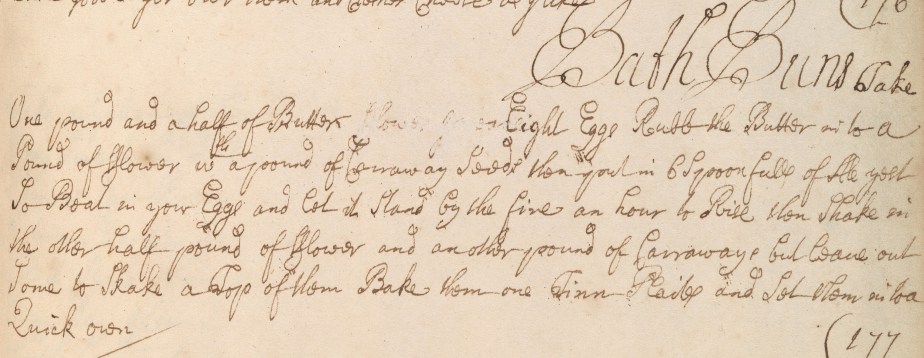

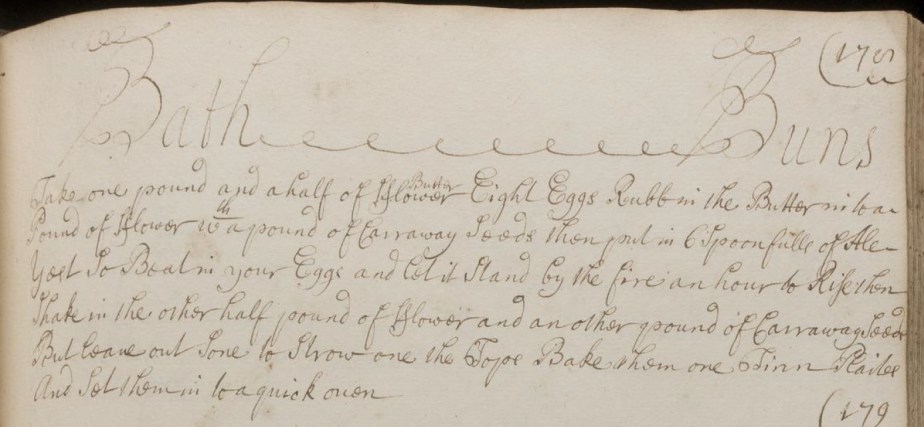

This recipe is particularly interesting because it has a twin, in another manuscript, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. This manuscript is one of the holdings at Yale University Library, and are both written in the same handwriting, possibly that of a scribe. They are mostly similar, but not exact copies. My guess is that one was copied from the other, with edits being made to exclude recipes not liked and including new recipes in the copy. With this in mind, I’m of the opinion that the Wellcome Collection manuscript is the copy. Below is the potential ‘original’.

All of which is an interesting detour, but doesn’t really get us an enjoyable Bath Bun that respects the traditions of the original, but is also acceptable to our 21st century tastes. Fear not, for galloping to our rescue comes a heroine for the ages: Mrs Bridget Ilbert (1712-1790), daughter of the 6th Earl of Devon and the wife of William Ilbert of Bowringsleigh, Devon.

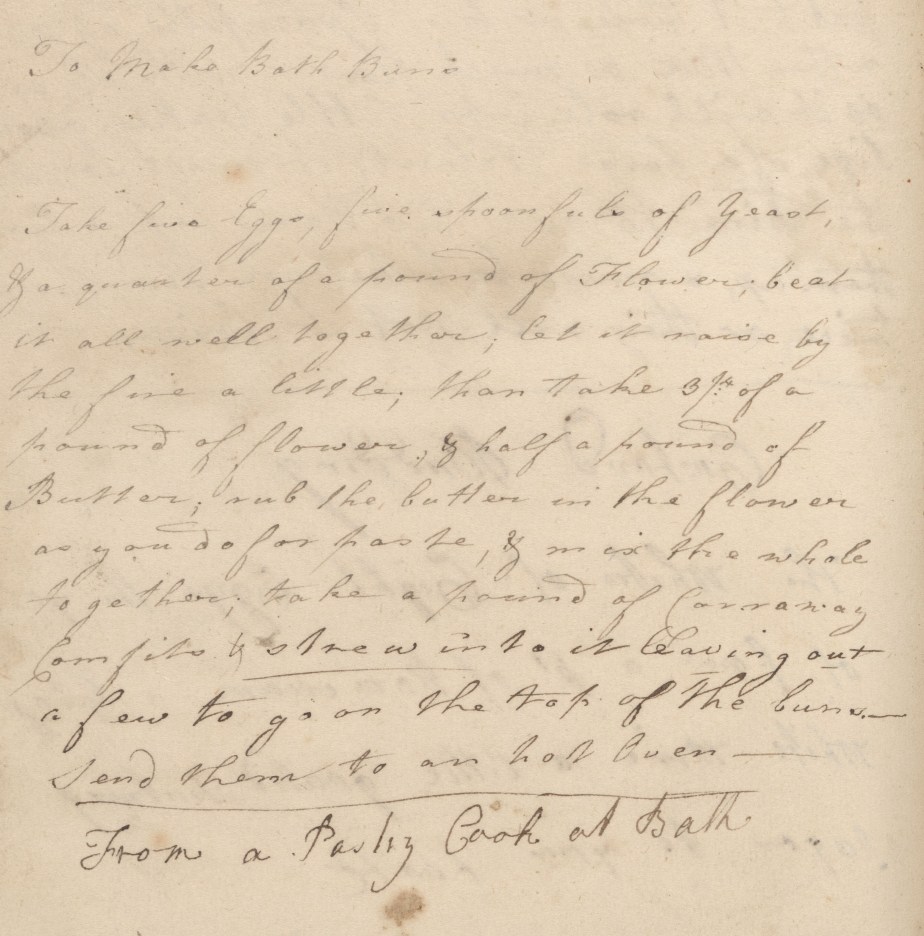

Bridget’s manuscript is held at The Wellcome Collection, and one of the recipes within is for Bath Buns. I particularly like this recipe because it comes with the added credentials of being “From a Pastry Cook at Bath” – and you can’t get much better than that. The recipe is undated, unfortunately, but it is not too big a stretch to allocate a date in the general area of early-to-mid 18th century.

Original 18thC Bath Buns

You can bake these on baking sheets or in silicone moulds. I used a mould like this, and had dough enough left over to make 4 free-form buns in the photo at the top of the page.

Makes 10-12 buns.

225g plain flour – divided

115g unsalted butter

1 sachet fast action yeast

2 large eggs

2tbs warm water

1tbs caraway seeds

100g crystallised sugar

1 large egg for glazing

milk

more crystallised sugar for finishing

a few caraway seeds to sprinkle

- Crack the eggs into the bowl of a stand mixer and add the yeast, water and 50g of flour.

- Whisk together thoroughly, then set aside to rise for 20 minutes.

- Prepare your baking items – parchment paper on baking sheets if baking ‘free-form’, butter your silicone moulds if using.

- Put the remaining flour and the butter into a food processor and blitz until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs.

- Add the butter mixture to the yeast mixture, together with the caraway seeds and mix thoroughly to a smooth paste.

- Mix in 100g crystallised sugar.

- Spoon onto/into your prepared baking items. 50g of dough makes an elegant size. Try and make your dough sit up high in as round a shape as you can make. N/A if baking in moulds.

- Whisk the egg with half an egg-shell of milk.

- Brush the egg glaze over the buns.

- Add a scattering of crystallised sugar onto the top of each bun, followed by a pinch of caraway seeds.

- Allow to rise for 30-45 minutes, depending on how warm your kitchen is. There won’t be a huge rise, because of all the sugar and butter.

- Heat the oven to 180°C, 160°C Fan.

- Bake for 15-20 minutes until golden brown. The bottoms of the buns will be slightly brown when baked.

- Allow to cool for 10 minutes to firm up before transferring to a wire rack to cool completely.

- Best served fresh.

- Store in an airtight container.

- To reheat before serving, microwave briefly, 10 seconds per bun, i.e. for 4 buns, zap them for 40 seconds.