There are many traditional foods associated with All Hallow’s Eve/Hallowe’en, November Night, but one which might be new (and deliciously simple to prepare), is the Irish potato dish of Colcannon.

Back in the beforetimes, when cakes of bairín breac were considered a luxury, people used to celebrate All Hallow’s Eve with a big pot of Colcannon. A ring was hidden in the depths of the creamy, mashed potatoes, and whoever ended up with it on their spoon, was said to be going to be the first to marry, within the next 12 months.

There aren’t many Irish cookery books of this time, so my favourite place to find accounts of the Irish food actually eaten by the population (as opposed to some publisher’s imagined scenario), is The School’s Collection at the National Folklore Collection, held at University College, Dublin. The Schools Project was an ambitious and wide-ranging collection of everything to do with Irish Folklore and Culture, gathered and recorded by school pupils between 1937 and 1939. More information about the project can be found here.

With information gathered from all across the country, it is fascinating to see both the common threads that bind the Irish people together, as well as discover the little differences that make each community unique. For instance, you might be aware of the popular Irish potato dish of Boxty, you might also be aware that it can be served in three different ways (loaf, dumplings, pan), but you might be surprised to learn that The Schools Collection contains over 150 different ways of making Boxty. I recently wrote a paper about this, the appendices of which, including the list of 150+ different ways of making Boxty, you can access here.

So it is, to a certain extent, with Colcannon. It also appears under the names Brúitín, Brúchin, Champ and Poundies, to name but a few. “No, no no!” I hear you exclaim, “Champ is its own thing! It’s made with spring onions!”

Well yes, but actually no.

It might actually be a Stampy/Boxty situation, where the same dish has different names, depending on the part of the country you come from. I shall be looking into this more soon.

Similarly, there can be interpretation as to what exactly the dish comprises. At it’s simplest, it is cooked potatoes, mashed with a little milk, pepper and salt, and served in a mound with a lump of butter in the middle. It is eaten by scooping some potato from around the edge and then dipping it in the growing pool of melted butter in the middle before consuming.

Many accounts of Colcannon have additional items of flavouring added. “A bit of greenery” is probably the easiest way to describe a large proportion of them, which include young (spring) onion, chives, nettles, leeks, shredded cooked cabbage or kale, parsley, regular onions.

The accompaniments can be anything you enjoy, but traditionally they include: sweet milk, buttermilk or sowans to drink, and crisp, crunchy oat bread (oatcakes) to use as a scoop.

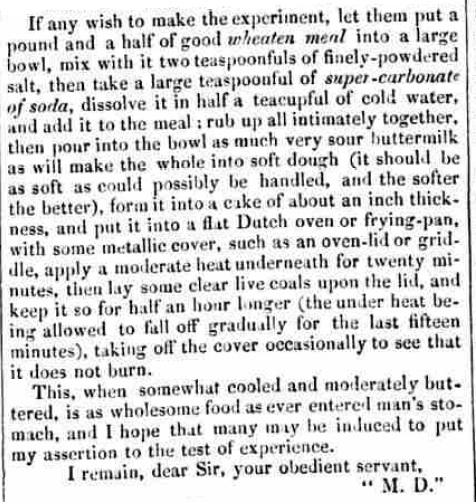

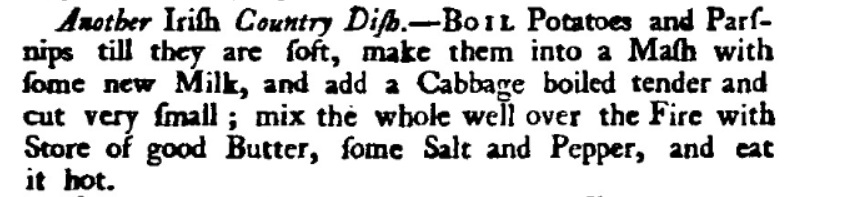

I was delighted to find just how old the dish of Colcannon is: there’s mention of it back in the eighteenth century. William Ellis (1750) includes a recipe for an “Irish Country Dish” in his The Country Housewife’s Family Companion, p366.

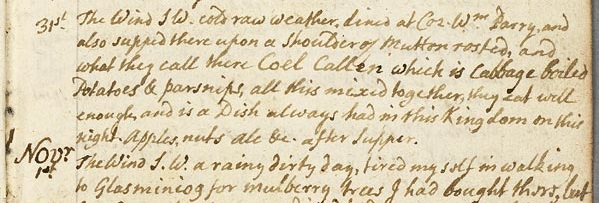

And Welsh diarist William Bulkeley (1691-1751), whose diaries are kept at Bangor University, mentions dining on “Coel Callen” at Halloween in 1735, whilst on a trip to Ireland.

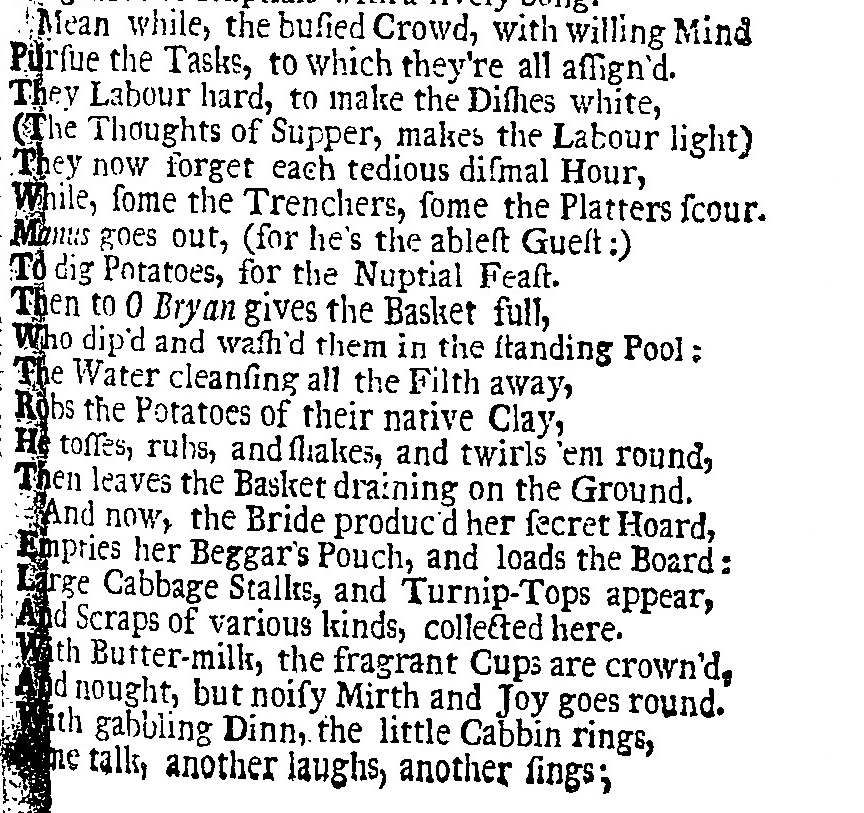

Even earlier, a poem published in Dublin in 1723, speaks of what certainly seems to be a dish of Colcannon being prepared for a wedding feast.

Colcannon

This is more of a guideline than hard-and-fast recipe. Use quantities to your own personal needs and taste.

potatoes

greenery

milk

salt & pepper

butter

ring (optional)

- Cook your potatoes. The method doesn’t really matter: boil or bake. The important detail is to mash them smooth whilst hot. I use a ricer to make sure all lumps have been dealt with, but you can also press them through a coarse sieve or use some elbow grease and a masher utensil.

- Smooth out the mixture by adding milk. NB Use hot milk, otherwise you run the risk of cooling down your potatoes too much. If you’re using any kind of onion, you might like to simmer them in milk for 10 minutes to both flavour the milk and reduce the harshness of the onions themselves. Strain out the onions, keeping the warm milk for mixing, and chop the onions finely – or to your taste. Cover and keep hot while the greens are prepared.

- Add your greens – this may be in the form of herbs (chives/parsley) green onions/spring onions/cibol/leeks, Savoy cabbage, spring greens, kale, sweetheart cabbage, white cabbage, Brussels sprouts, spinach, nettles, etc. The cabbage and/or leeks should be shredded to your liking (fine/coarse) and blanched/steamed for five minutes. Add sufficient to your own personal taste.

- When everything is piping hot, serve your Colcannon in a large communal dish, with a generous amount of butter in a hollow in the centre, and hand round spoons for all. Don’t forget to pop a ring into the mix before serving, if matrimony is in your plans.