Wotchers!

We’re back to the history books this week, with an original Simnel recipe from the 1650s. And yes, I’m exactly a week late, since they were originally enjoyed on Mid-Lent Sunday, which has, over the years, segued into Mothering Sunday/Mothers’ Day. Still, they were popular throughout the Easter celebrations, so there’s still time to rustle some up if you feel inspired.

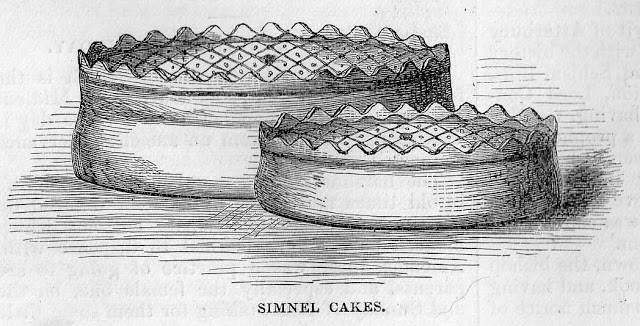

Three regions of Britain lay claim to strong Simnel traditions: Devizes in Wiltshire, Bury in Lancashire and Shrewsbury in Shropshire. The Devises Simnel is recorded as being star-shaped and without a crust, and the Bury Simnel is traditionally flat, but the Shrewsbury Simnel was the most popular and which went on to develop into the Easter cake we know today.

The Shrewsbury Simnel of 350 years ago was much different to the traditional almond-paste-filled cake made today. Originally, it was an enriched and fruited yeast dough wrapped in a plain, yeasted dough,and then boiled before being baked, in a method similar to the way modern bagels are made. There are similarities with today’s Scottish Black Bun, the difference being both the use of unleavened pastry and the much richer filling of the northern version.

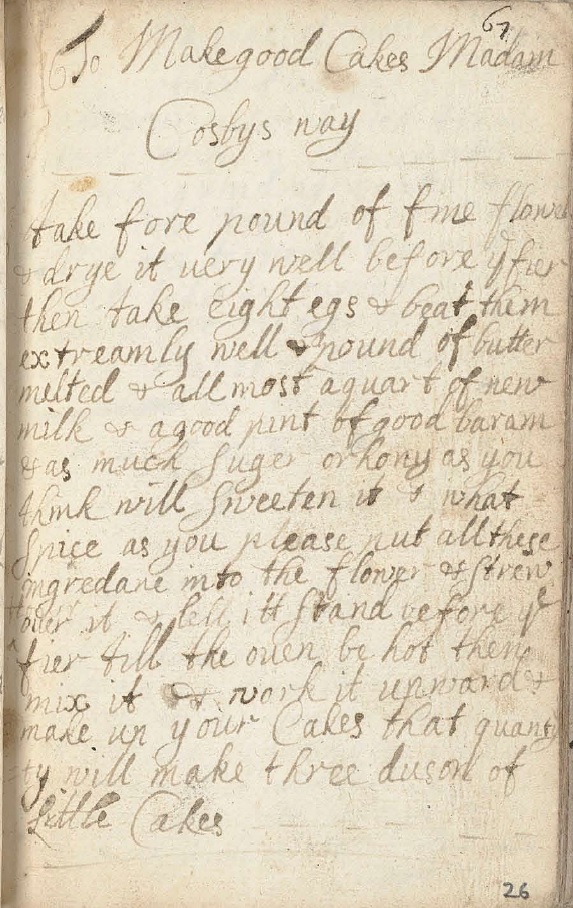

Whilst descriptions and images of what Simnels looked like are well known, recipes have, to a great extent, been either extremely vague or pretty much guess-work, as all the original recipes have vanished over the years.

Until now.

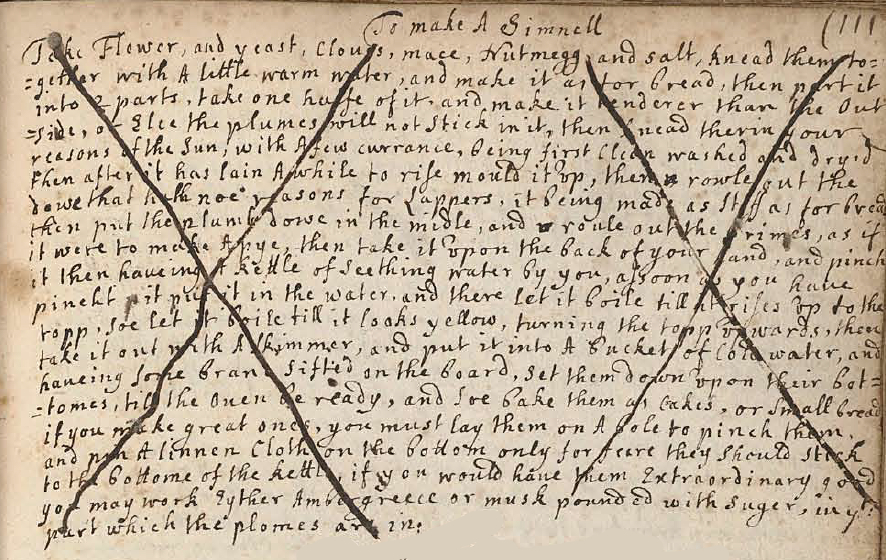

For, as I was browsing through the digitised 17th century manuscripts of The Wellcome Library, I found a recipe for a Simnell. It’s made in the traditional manner of first boiling then baking, and someone has subsequently crossed it out, but it’s still legible and much older than anything I’ve been able to find until now, so in terms of authenticity, that’s good enough for me.

It’s a little sparse on quantities and details such as cooking times and temperatures, but there was enough for me to muddle along with my own interpretation. Interestingly, there’s no mention of the traditional saffron flavouring, these cakes being ‘gilded’ with egg-yolk glaze only, so maybe the use of this spice was a later development.

It also fails to mention what size these festive cakes were. There’s anecdotal evidence from several 19th century sources, that claim Shrewsbury Simnels were made in all sizes from miniature up to cushion size, and also of them being sent all over the country as gifts. One account tells of a bemused recipient using hers as a footstool, not being aware that there was a delicious cake within the double-cooked crust. I opted for pork-pie-sized cakes for a couple of reasons:

- The recipe says to “take it upon the back of your hand and pinch it” – difficult for a large sized cake.

- The baking instructions are “bake them as cakes or small bread” – so bread roll size rather than loaf sized.

- Mention I found of cymlings or simnels in the notes of early American settlers on the local vegetation.

- In 1690, the Reverend John Banister recorded in his Natural History [of Virginia]

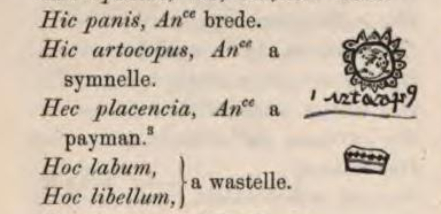

We plant also Cucumbers & Pompions, the common, & the Indian kind with a long narrow neck, which from them we call a Cushaw. Of Melopepones or the lesser sort of Pompions there is also great variety, all which go by the Indian name of Macocks; yet the Clypeatae are sometimes called Simnels & because these others also from the Lenten Cake of that name which some of them very much resemble.

- Earlier, in A Description of New Albion (1648), Beauchamp Plantagenet (what an AWESOME name!) observed “strawberries, mulberries, symnels, maycocks, and horns, like cucumbers” on Palmer’s Isle (now called Garrett Island) at the northern end of Chesapeake Bay.

The vegetable they both refer to is nowadays more commonly called the pattypan squash.

The recipe below will make four, individual-sized Simnels. Feel free to enrich the filling for the dough even more by adding extra fruit, spice peel, sugar, butter and eggs. The mix below, however, will make a delicately spiced and fruited tea bread that is delicious on its own as well as spread with butter and/or toasted. Provided your Simnels don’t burst their seams during baking, the hard outer dough will ensure that they keep very well for a couple of weeks.

Shrewsbury Simnels

For the plain dough:

250g white bread flour

0.5tsp salt

0.5tsp mace

0.5tsp nutmeg

0.25tsp cloves

1/2 sachet easy-blend, fast-action yeast

warm water to mix

- Sift the flour, salt, spices and yeast into a bowl.

- Slowly add enough warm water to bring the ingredients together into a firm dough.

- Knead for 10 minutes.

- Put into an oiled bowl and cover with plastic film.

- Set aside to rise for 1 hour.

For the filling dough:

250g white bread flour

0.5tsp salt

0.5tsp mace

0.5tsp nutmeg

0.25tsp cloves

1/2 sachet easy-blend, fast-action yeast

1 large egg

60ml double cream

50g butter

2tbs sugar

100g raisins

100g currants

2 large egg yolks for glazing.

- Sift the flour, salt, spices and yeast into a bowl.

- Cut the butter into small pieces and put into a pan with the cream and the sugar.

- Warm gently until the butter has melted and the sugar has dissolved

- Whisk the egg and add to the warmed ingredients. NB Make sure they aren’t so hot that they cook the egg.

- Add the liquid ingredients to the flour mixture and knead for 10 minutes.

- Put into an oiled bowl and cover with plastic film.

- Set aside to rise for 1 hour.

- Put a large pan of water on the cooker to boil. I use my preserving pan. Do it now because it will take practically the whole hour to come to heat up.

- When the dough has doubled in size, knead in the raisins and currants.

To assemble the cakes:

- Divide the plain dough into 8 even pieces and roll each piece out thinly (3mm).

- Line 4 small deep pie/tart tins with cling film. This will help turn out the finished cakes.

- Use 4 pieces of plain dough to line the tart tins. Leave the excess dough hanging over the edge of the tins, as it will help in forming a good seal around the cake dough.

- Chill in the fridge together with the remaining pieces of dough, which will form the lids, for 20 minutes. This chilling will firm up the dough and make it easier to form the crust on the cakes.

- Divide the fruit dough into four and knead until firm and smooth. If you’ve added extra fruit or your tins are on the small side, you may need to reduce the size of the dough balls.

- Remove the chilled dough from the fridge. It is best to form one cake and then place it in the hot water immediately. If left to one side while you make the other cakes, the dough will warm up, rise and potentially burst its seals.

- Place a ball of fruit dough in each tin.

- Moisten the edges of the dough with water and cover with one of the dough lids.

- Press firmly and pinch together to form a seal around the fruit filling. Trim any excess dough.

- Crimp the edges of the cake according to your own design.

- Fill a large bowl with cold water.

- When the water is simmering, place each cake on a skimmer and slowly lower into the water. It will sink to the bottom of the pan initially. When the cake rises, use a skimmer to gently turn it over so that the lid cooks for about a minute.

- Lift the cake from the hot water and lower it gently into the bowl of cold water.

- When cooled, set the cake onto a silicon sheet (so that it doesn’t stick) to dry.

- Repeat for the remaining cakes.

- Preheat the oven to 170°C, 150°C Fan.

- Line a baking sheet with parchment.

- Place the Simnels onto the baking sheet.

- Brush with beaten egg-yolk to glaze.

- Bake for 45-50 minutes until firm and golden. They should sound hollow when tapped on the bottom. Don’t be tempted to take them out too early, even with the dip in the hot water, these will take a relatively long time to bake.

- Cool on a wire rack.