Jane Parker, 1651 adapted from The Good Huswife’s Jewell, 1587

I was drawn to this recipe because it involved spicing strawberries and baking them in pastry, both details being so different from how we tend to use strawberries today. Originally, I was delighted to find the recipe in Jane Parker’s manuscript recipe book¹ but some months later, when I found an earlier version in a cookery book from the previous century, it became at once both more interesting and more delightful. Thomas Dawson’s recipe for strawberry tart², was published in the middle of the reign of Elizabeth I, and is, in all honesty, a little sparse on the level of detail to which our 21st century eyes are accustomed when it comes to recipes. Indeed, it is so brief I can quote it in full below:

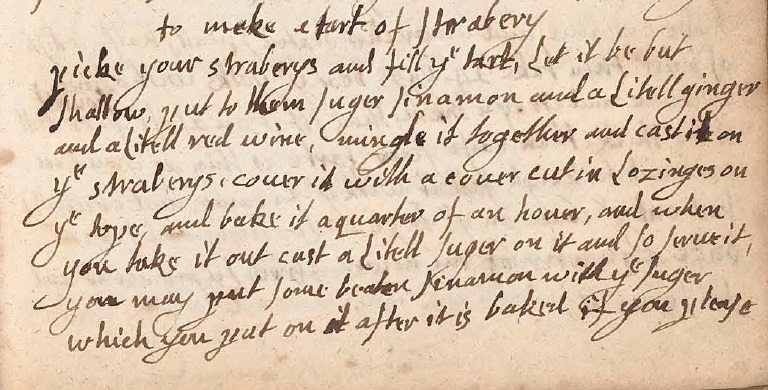

To make a tart of strawberries

Wash your strawberries and put them into your Tarte and season them with sugar, cinnamon, and ginger and put in a little red wine into them.

No quantities, cooking times, or even mention of a pastry recipe. It would appear Jane Parker also thought a little extra detail was required, and her recipe is as follows:

Whilst there’s still no pastry recipe, we do have more detail in terms of presentation: the tart should be shallow, the pastry lid should have diamond cutouts, baking time of 15 minutes and a sprinkling of spiced sugar over the baked tart. These additional details, to my mind, highlight the fact that, even if she didn’t actually make the tart herself, Jane Parker definitely got the recipe from someone who had, as these details are precisely the kind of personal touches an experienced cook would note down for future reference.

After centuries of refinement, the strawberries we now use are impressively large but much milder in flavour than those that would have been used for this originally Elizabethan tart. If you can find sufficient wild strawberries either to mix with your ordinary strawberries or, decadently, to use on their own, their deep aromatic flavour, together with the wine and spices, will make for a much more robust flavour to this unusual Tudor tart.

Spiced Strawberry Tart

1 batch of Sweet Shortcrust Pastry

600g fresh strawberries

3 tbs caster sugar

1tbs cornflour

1tsp ground cinnamon

1 tsp ground ginger

½ tsp coarse ground black pepper

60ml red wine or port

Milk for glazing

1tbs caster sugar

1tsb ground cinnamon

- Preheat the oven to 200°C/180°C fan/gas 6.

- Roll out the shortcrust pastry thinly. The thinner the pastry, the less time it will need in the oven and the freshness of the strawberries will be all the better for it.

- Cut out four lids for your tarts. Cut them generously so that there is sufficient pastry to form a seal with the pastry lining the tins. Use a small diamond cutter or any small shape, to cut a lattice into the lids. Be careful not to cut too close to the edge, otherwise they will be tricky to attach to the rest of the pastry.

- Gather the trimmings and re-roll the pastry.

- Grease and line four individual pie tins with the pastry. Let any excess pastry hang over the sides for now.

- Prepare the strawberries: Remove the stalks and cut into small pieces, either 4 or 8, depending on the size of the strawberries.

- Put the cut strawberries into a bowl and sprinkle over the red wine. Toss gently to coat.

- Mix the sugar, cornflour and spices together. Sprinkle over the strawberries and toss gently to mix.

- Divide the strawberry filling amongst the tins and smooth over.

- Moisten the edges of the pastry and place the lids over each tart. Press firmly to seal, then trim and crimp the edges

- Brush the tops with milk and bake for 12-15 minutes until the pastry is cooked and lightly golden.

- Mix the remaining caster sugar and cinnamon together and sprinkle over the hot pies.

- Cool on a wire rack.

¹ MS3769, Wellcome Library.

² The Good Huswife’s Jewell, 1587