I have a ‘lost’ recipe for you today – a spiced bun that has been known about, recorded and discussed for over 200 years, but for which there has been no recipe. Until now.

By Thomas Firminger Thiselton Dyer · 1876 p81

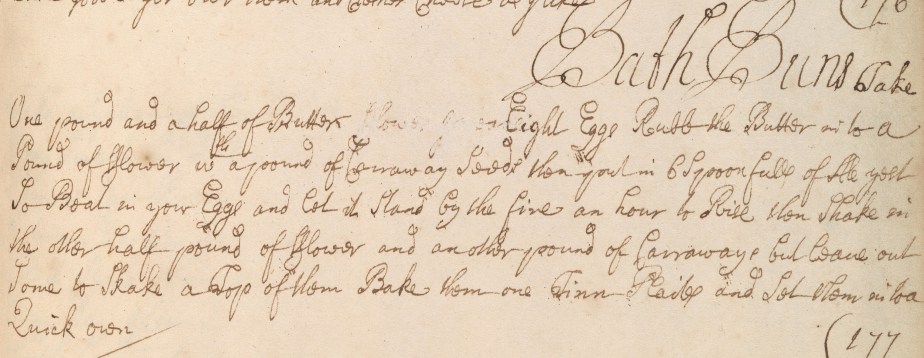

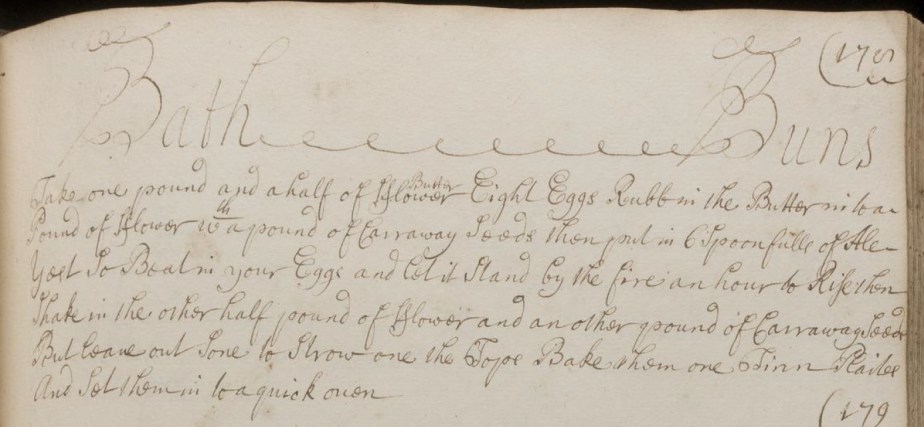

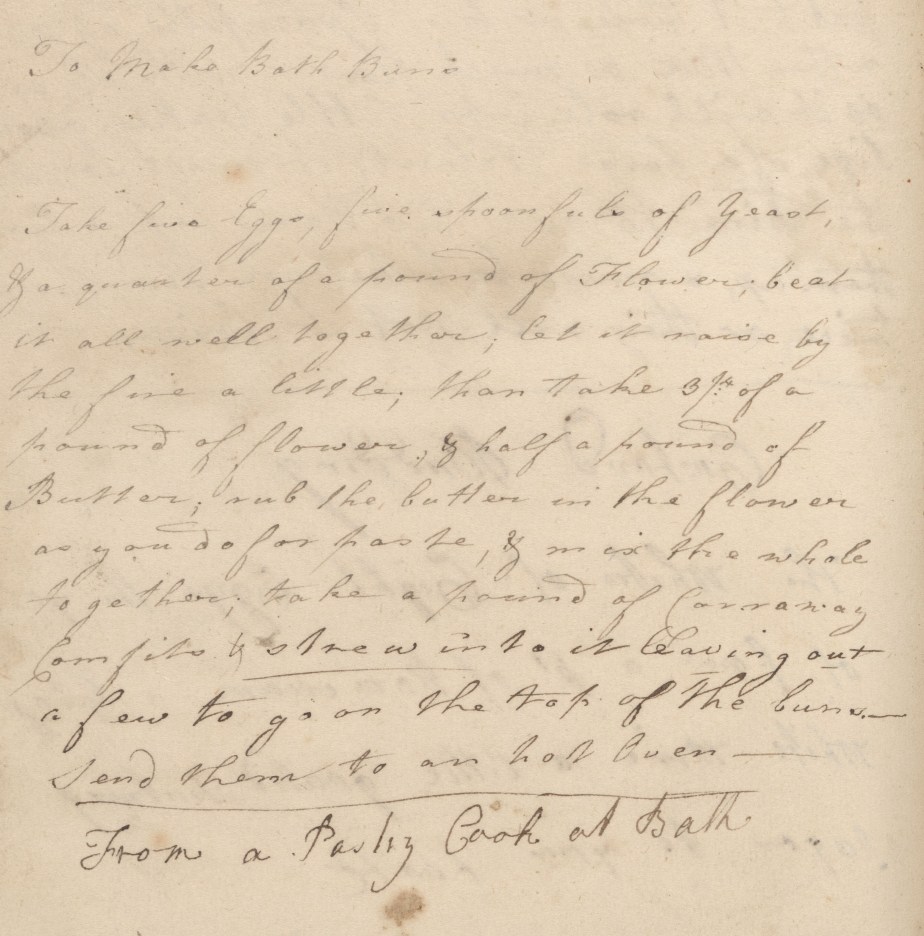

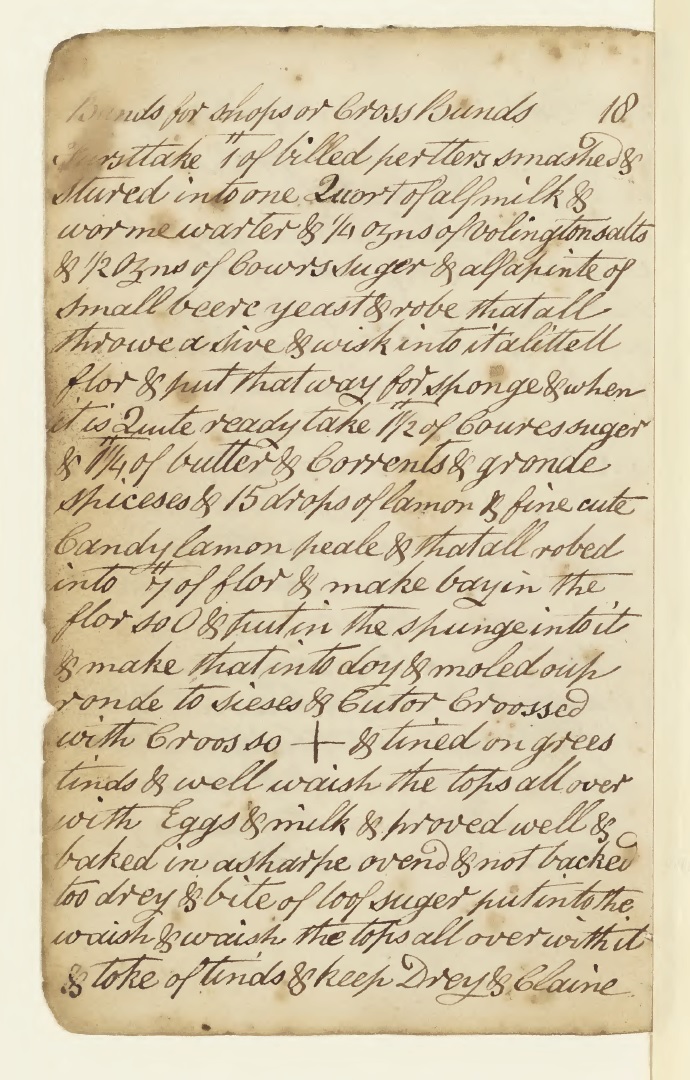

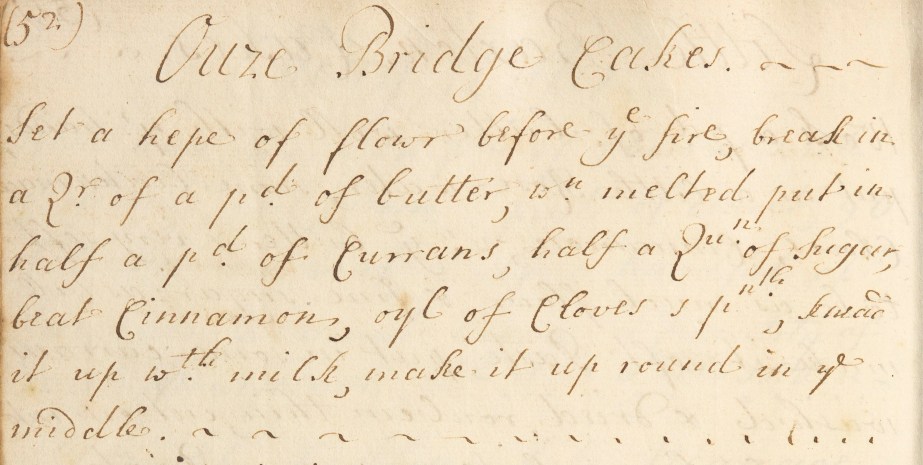

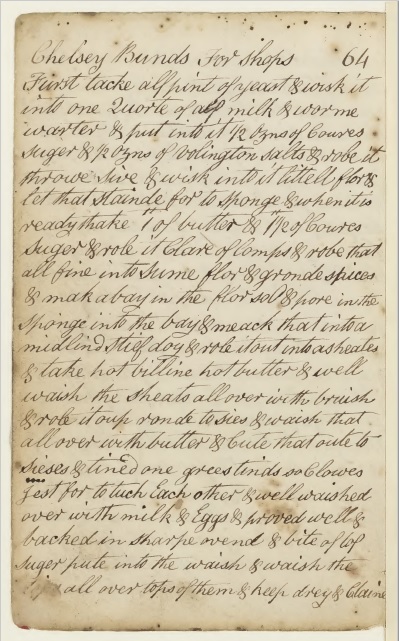

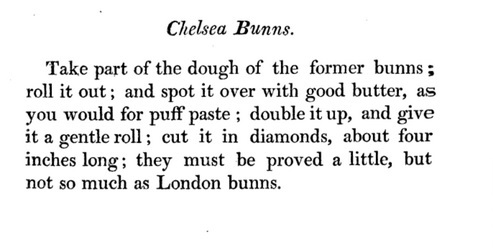

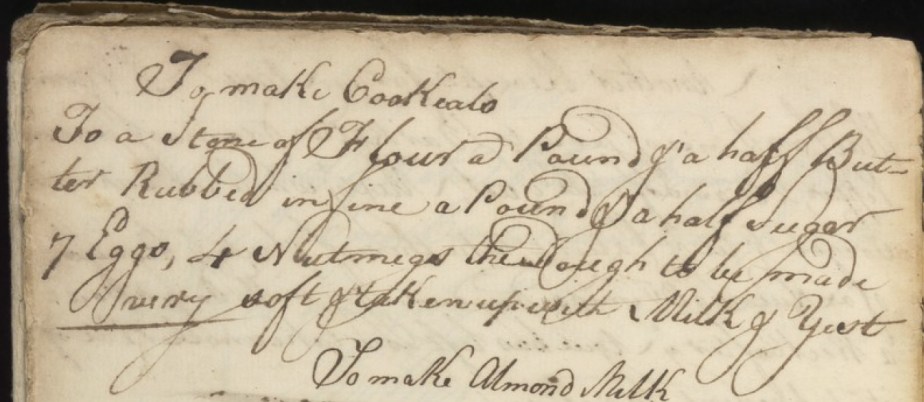

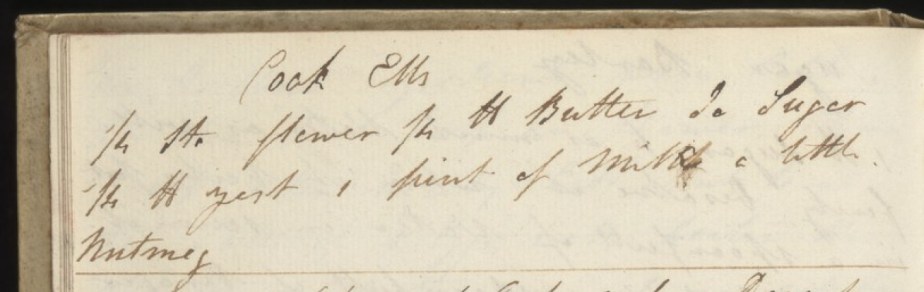

As luck would have it, I found not one but two recipes buried in the handwritten manuscripts held by The Wellcome Collection.

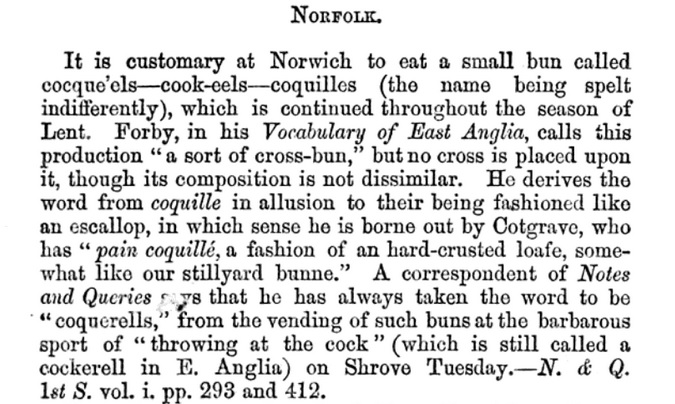

The earliest mention of Cookeels is found in Robert Forby’s The Vocabulary of East Anglia.

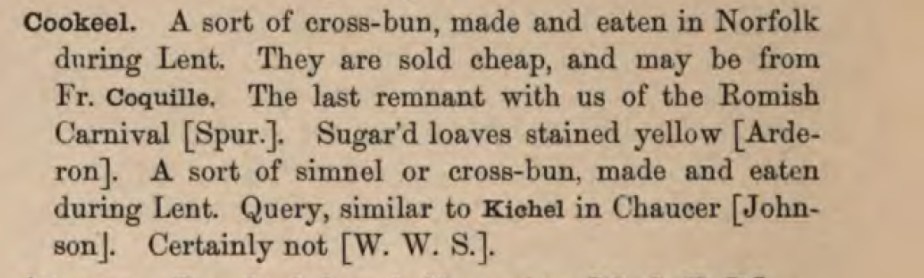

Cookeel: A sort of cross-bun, made and eaten in Norfolk during Lent. They are sold cheap and may be from Fr. Coquille.

The Vocabulary of East Anglia, Robert Forby, 1830, p76.

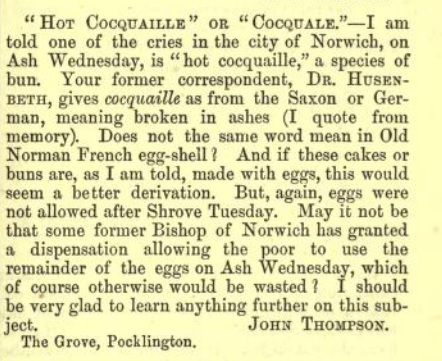

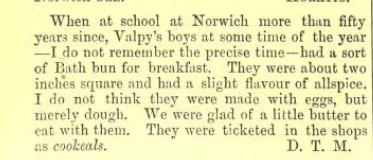

This definition is expanded upon throughout the nineteenth century as more and more academics weigh in with their opinion.

Something that became more and more apparent, is the somewhat lackadaisical approach to the spelling of these baked items. This is also true of the names of the two manuscript recipes, to whit Cookeals and Cock Ells:

Confession time, I do like to get the the truth of the matter when it comes to recipe names and history. Love a great backstory, cannot be doing with made-up rubbish. So with all these different names, I decided to drill down and see if I couldn’t get to the bottom of it all (this phrase will come back to haunt me shortly).

I don’t think there’s much merit in the name deriving from the French ‘coquille’ (shell): there’s no hard crust, due to the butter, milk and eggs, and no mention of them being shell-shaped. Similarly, I think naming them after the cockfighting pits is also a bit of a stretch. The various accounts seeme to waver between Cockeel and Cookeel, and neither of the handwritten recipes offer any definitive help.

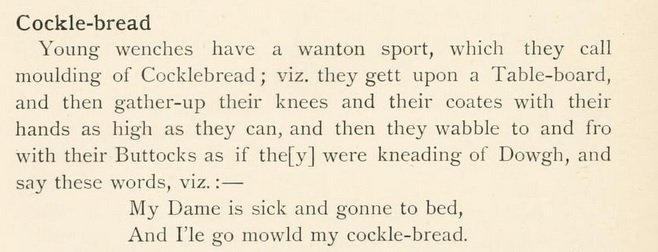

Playing around with the spelling, it turns out that Cockle bread is a thing:

“So far back as the time of Henry III., we find mention made of wassel bread, cockle bread and bread of treet corresponding with the three sorts of bread now in use, viz. white, wheaten and household bread.”

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 1, p157, 1852.

Cocklety bread has also been recorded in playground chants:

“The term ” Cockelty ” is still heard among our children at play. One of them squats on its haunches with the hands joined beneath the thighs, and being lifted by a couple of others who have hold by the bowed arms, it is swung backwards and forwards and bumped on the ground or against the wall, while continuing the words, “This is the way we make cockelty bread.”- -Robinson’s Whitby Glossary, p. 40.”

“The traditional games of England, Scotland, and Ireland” 1894-1898, Alice Bertha Gomme, p75

Delighted with this quaint image, I pursued Cockle Bread further – and immediately regretted that decision.

And before I knew it, I was learning that as an extension of this ribaldry, sometimes dough was actually kneaded this way, and then baked and fed to the person whom the girl wished to enamour.

ANYHOO……..Spice buns!

Cookeels

Makes 16

These soft, pillowy buns were enjoyed throughout the season of Lent. Unlike the more famous Good Friday buns, they contained no fruit and neither were they marked with a cross. One of the above anecdotes mentioned allspice as a seasoning, but neither of the recipes do, so we’re going to stick to nutmeg. Usually mixed with several other spices, the fact that these buns have just a single spice adds to their appeal. The enrichment of the egg, milk and butter makes the dough exceedingly soft and the baked bun incredibly tender of crumb. Delicious warm from the oven and freshly buttered, you can also enjoy them toasted with butter and cheese.

150ml water

150ml milk

1 large egg

100g butter

100g caster sugar

pinch of salt

450g strong white flour

2tsp ground nutmeg

1 sachet fast-action yeast

1 large egg yolk

2-3tbs milk

- Put the dry ingredients into a food processor and blitz until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs.

- Tip the mixture into a mixing bowl.

- Zap the water in the microwave for 1 minute. This should heat it but without boiling.

- Pour the milk into the hot water and stir. It should now be warm. Add the egg to the warm milk mixture and whisk thoroughly.

- Pour the milk mixture into the other ingredients and mix until the dough comes together. It will be very soft – too soft to knead – but it will become manageable once risen.

- Cover the mixing bowl with plastic wrap and set aside in a warm place to rise for 1 hour.

- Cover a large baking tray, or shallow oven shelf for preference, in baking parchment.

- Once the dough has risen, dust your work surface well with flour.

- Tip the dough out onto the flour and pat gently to deflate. Dust the surface with flour, then, with the help of a dough scraper, lift and fold the sides inwards and pat down. Continue the dusting and folding until the dough is firm enough to handle. The first time I made this, I put too much liquid in, but it only took three lots of folding to make it manageable.

- Pat the dough into a square. it will be roughly 20cm, but if it’s larger, that’s fine.

- Cut the dough into 16 pieces. The easiest way is to cut your square of dough into quarters, then cut each quarter into four.

- For each piece, fold in the edges of the dough, flip it over and roll into a ball under your hand.

- Set the shaped dough onto your prepared baking sheet. The dough will spread during rising/baking to the size of a teacake, so space them well apart (7-8cm).

- When all the dough has been shaped, cover lightly and set aside to rise for 30 minutes.

- Heat the oven to 180°C/160°C Fan.

- Whisk together the egg yolk and the milk and brush this glaze over your risen buns. You can use just milk if you prefer.

- Bake your buns for 20 minutes, turning the baking tray/shelf around after 10 minutes to help with even colouring.

- Remove from the oven and immediately cover with a clean cloth. This will trap the steam and ensure your buns are soft and pillowy when cooled.

- Store in an airtight container when cold.