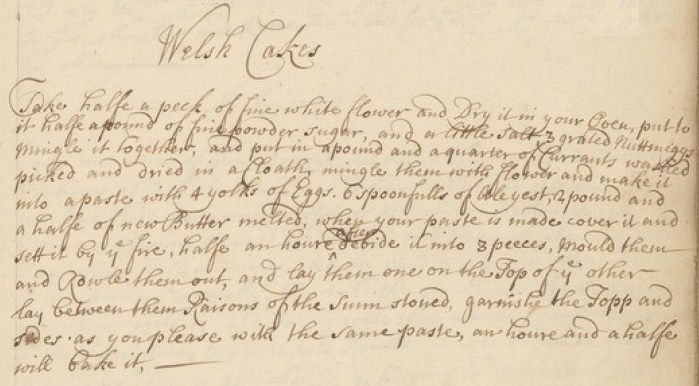

Jane Newton, circa 1675

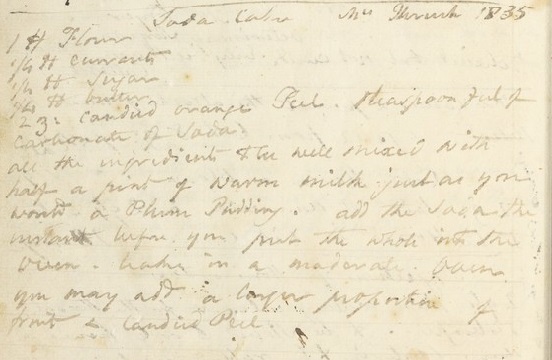

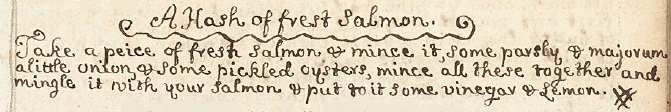

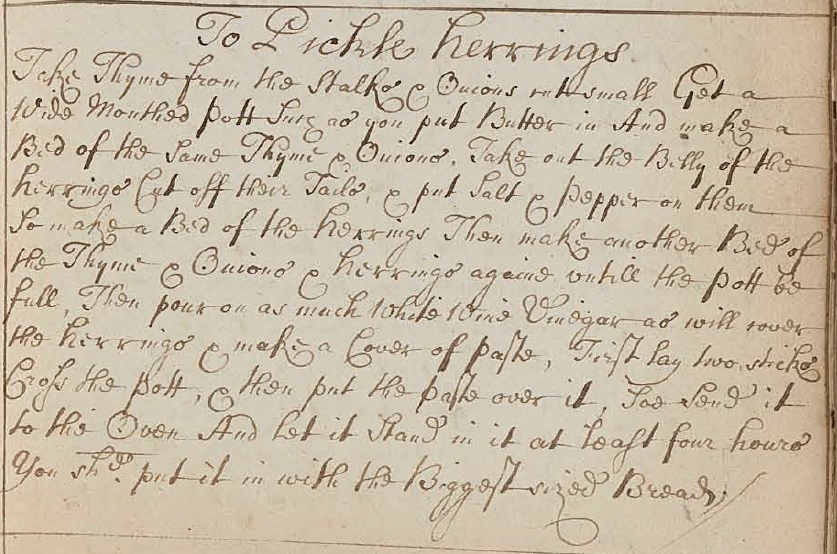

Jane Newton’s 17th century manuscript recipe book (MS1325 at The Wellcome Library) is unusual for the time, because it appears to have been written by the lady herself, rather than a scribe. It is meticulously set out, beginning with an alphabetical index and progressing through a range of recipes, informally grouped together: potages, roasts, boilings, collarings, puddings, picklings, tarts, wines and preserves.

The handwriting is regular, the lettering excessively flourished – Jane loves an upper-case letter and refuses to confine them to the beginning of sentences – the spelling quirky and capricious. The ink has faded to brown, but the scarlet margins and diligently underlined titles are still bright and bold.

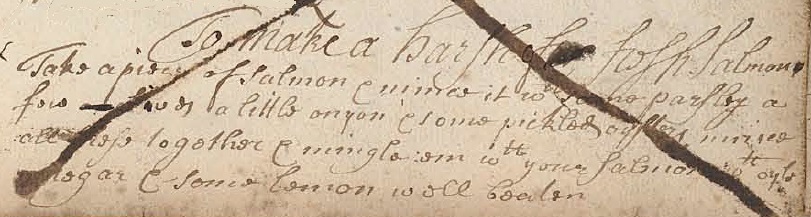

The book has a very informal tone, and on reading, it is possible to imagine Jane chattering away about her cookery recipes, complete with interruptions to her train of thought. In the recipe for Taffety Tarts, she gets as far as rolling out the pastry, only to leave the instructions hovering unfinished on the page as she then gets distracted into starting a recipe for Manchet. This too appears incomplete as, after setting the dough to rise, the recipe is hurriedly ended with the vague hand-wave of “yn bake itt.”.

The title of this miniature pie recipe is a perfect example of the informal tone of most of the book. In the early pages, Jane closes out a recipe for Partridge Pottage with the following comment:

This Pottage is proper to bee Garnished wth Pitti Patties or Little Pa∫sts a thing never yet in Print And I shall give yow the be∫t diretton for the makeing them when I treat of Bakemeates wch wil bee thereafter given yow

It takes more than twenty pages for this recipe to turn up. Rather than a succinct yet descriptive title, Jane opts to call it To make the Pufes I was Speaking of before in my Pottage. I don’t know about you, but I can almost hear Jane’s vague introductory “Oh…you know…. those things…. pastry bits…. whatchamacallits…. the ones I was talking about earlier!” and all-too-easily picture the accompanying distracted, flapping hand.

Jane was, justifiably, very proud of these tasty morsels:

The∫e are a thing wch is delightfull to the Eater & is not a u∫uall thing at many Tables to be had and Invented by an Italian

These pies are a true déja food recipe through the use of cooked meat in their composition. Although I’ve chosen to use just chicken, the original recipe suggests a combination of both chicken and veal. Other suitable alternatives would be most poultry and pork. The filling also differs from most modern pies in that it contains neither sauce nor gravy. A mere squeeze of orange juice, possibly a Seville, and the moisture in the fresh ingredients keeps the filling from drying out and keeps the pastry from becoming soggy during baking. Once baked, a few drops of chicken stock are added into the pies to supply both seasoning and lusciousness.

The most unusual detail for these little savoury pies is the inclusion of a grape in the middle. Originally, these would have been from bunches taken as thinnings of the vines commonly grown by the great houses (there’s never enough room to allow every bunch of grapes to ripen) so they would be small, underripe and quite sharp to the taste. In the baking they soften a little and provide a bright burst of freshness to the cooked pie. Small green gooseberries work equally well, if you don’t have a vine to hand.

Jane suggests serving these as garnishes to the aforementioned pottage (meaty soup) or even on a dish by themselves. I would widen this by recommending including them in lunchboxes, picnics or as nibbles/appetisers.

Mini Chicken & Bacon Pies

Makes 20 mini pies

shortcrust pastry – made with 300g flour

1 sheet ready rolled puff pastry.

150g cooked chicken

60g smoked, dry-cured streaky bacon – about 4 rashers

3tbs finely chopped fresh parsley(10g)

1tbs fresh thyme, stripped from the stalks

2 rounded tbs chopped shallot (1 ’round’ or ½ a smallish ‘banana’ shallot)

¼ tsp ground white pepper

a pinch of salt

juice of ½ an orange – about 2tbs/30ml

20 small, sharp grapes/gooseberries

Egg for glazing

100ml well-flavoured chicken stock

- Dice the chicken and bacon finely and stir together with the herbs, onion and seasoning.

- Add the orange juice and stir to combine.

- Preheat the oven to 220°C, 200°C Fan.

- Roll out the shortcrust pastry, cut out 20 rounds and line the greased cups of a mini muffin tin.

- Spoon a little of the mixture into the cups, place a grape in top, then cover with more of the filling mixture.

- Dampen the edges of the pastry with a little water.

- Cut out 20 lids from the puff pastry and press them gently on top of the mini pies.

- Trim any excess pastry.

- Brush over with beaten egg and cut a small hole in the top of each pastry lid – a plastic straw works well.

- Bake for 15-18 minutes until the pastry is cooked, the lids puffed and golden.

- Use a small funnel or teaspoon to pour a little chicken stock into each pie to moisten the filling.

- Cool on a wire rack.

- Serve warm.