Three recipes for you this week, all originating from a single idea. I thought I’d take the opportunity to show how it is possible to play with recipes you already know and love, and adapt a favourite one to different flavourings and pairings.

I was catching up on the latest season of the Great British Bake Off the other day, and for Biscuit Week the bakers were asked to make Viennese Whirls for their signature bake. I made a similar biscuit in Season Two – except I called them Melting Moments – so I was interested to see what variations this season’s bakers would bring to the table.

The range was wide and the flavour combinations a mix of both unusual and familiar (you can read more details on the specific flavourings/pairings here), and I got to pondering what I would have made. I think I would probably have gone savoury, and what better place to start than with my original recipe, and seeing if it could be tweaked to a more salty flavouring.

Obviously, the main stumbling block is the Melting Moments I made were sweet. Messing about with other recipes I’ve found that substituting cheese for the sugar on a 1:1 basis can get you a long way down the savoury route. I didn’t want the biscuits to spread much, and I also didn’t want the cheese to clump together and produce blobs, so rather than grating fresh from a block, I chose to use already-finely-grated Parmesan cheese (still fresh, just not grated by me). Test Batch 1 (a half batch of the original quantities – another Top Tip when you’re experimenting – no need for a full batch of anything until you get it right) was a straight substitution of cheese for sugar. To compliment the cheese, I also added dry mustard and ground nutmeg, as well as salt.

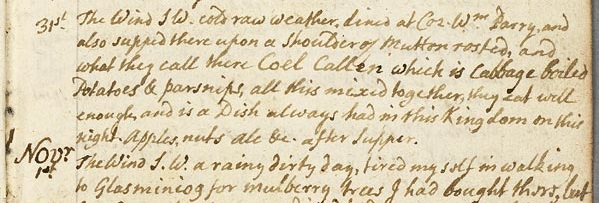

The results were cheesy-ish but also a little greasy, so Test Batch 2 involved more cheese (for taste) and more cornflour (to help with the greasiness). Batch 1 also didn’t hold their shape very well, but when I was looking at the tweaked ingredient proportions, I saw they were veering close to those of the best kind of shortbread (I made so many batches the proportions are burned into my brain), and so I opted to bake the dough in a shallow-sided pan, just like the shortbread. I didn’t want to dough to blister or rise up, so I poked holes in the dough, also like shortbread. The baking was also done long and low, and the result was absolutely delicious: strong cheese flavour, with the subtle hints of the mustard and the nutmeg rounding it out. The long, slow baking had toasted the cheese particles, which now had the bonus of adding little nuggets of crunchiness to the texture. Finally, cutting the cooked dough into pieces hot from the oven, then putting the tin back in as the oven cooled, made for a gloriously toasted flavour and appearance. It was an amazingly savoury, cheesy, shortbread, but a bit far from a Viennese Whirl.

In addition, the original prompt required a filling of some sort, so I went back to the drawing board and recalled a recipe for a favourite pull-apart bread flavoured with walnuts and blue cheese. After toying with the idea of adding the nuts to the biscuit filling, I opted for adding them to the biscuit dough, and making the filling with blue cheese.

Test Batch 2 was much better in terms of crumbly texture, but the flavour of the walnuts wasn’t really there. So for what would be the final Test Batch, I reduced the Parmesan cheese to keep it savoury but not intrusive, and toasted the walnuts. I kept the amount of cornflour the same, since walnuts have their own oil and this would also need to be absorbed in order to keep the biscuit texture. The result was just what I was going for: crumbly melt in the mouth biscuit texture, robust walnut taste with just a hint of Parmesan.

The last step was to sort out the filling. I opted for Saint Agur, which is a soft and creamy, relatively mild blue cheese, and mixed it with some cream cheese to make it pipe-able. These biscuits lack the piped form of traditional Melting Moments, so adding the swirl in the filling is a neat compromise. If you’re a blue cheese fiend, then use stronger-flavoured cheeses by all means – you might have to work a little harder to get them blended with the cream cheese. I don’t usually recommend brands, but Philadelphia cream cheese has the firmness and creaminess that is just perfect here. If you use a different cream cheese and the result seems a little watery or not as dense as you would like, you can firm it up by placing it directly onto 4-6 folded layers of kitchen roll (in a sealable plastic box or similar) and chilling in the fridge overnight. The excess moisture will be drawn out into the paper towel, firming the cheese mixture up and making the mix easier to pipe. If you don’t have the time to do this, just use your cream/blue cheese mixture as a dip. There is also a Saint Agur Blue Crème product with the cream cheese already mixed in. It is very smooth indeed, but too soft to pipe. Perfect to use as a dip, though.

So there we are. Arguably three different recipes (yes, yes – I know the dip is a bit of a stretch, recipe-wise) from a single inspiration. I do hope you try them, and then have fun experimenting with tweaking your own recipe favourites.

Cheese Shortbread

125g plain flour

50g cornflour

125g unsalted butter – chilled

½tsp salt

½tsp ground nutmeg

½tsp yellow mustard powder

50g ground Parmesan cheese

- Heat the oven to 160°C, 140°C Fan.

- Line a shallow baking tin with parchment. I used one of dimensions 26cm x 18cm, but a 20cm square would also work.

- Put all of the ingredients into a food processor and blitz in brief bursts until the mixture comes together in a soft paste.

- Press the paste into the prepared tin and smooth over. Using a skewer or a cocktail stick, poke holes evenly over the whole surface area.

- Bake for 30 minutes, turning the tin around halfway through to ensure even baking.

- When baked, turn off the oven, remove the shortbread and cut into pieces. I prefer to use my metal dough scraper, which is super thin, to get nice, clean, sharp cuts.

- Put the shortbread back into the cooling oven, to finish off.

- When cold, store in an airtight container.

Walnut & Blue Cheese Melting Moments

30g walnuts

125g plain flour

50g cornflour

125g unsalted butter – chilled

½tsp salt

30g ground Parmesan cheese

- Toast the walnuts:

- Heat the oven to 200°C, 180°C Fan.

- Lay the nuts on a baking tray lined with parchment paper.

- Bake for 8 minutes, turning the tray around halfway through to ensure even browning.

- Set aside until cool, then chop with a knife into small pieces.

- Put the remaining ingredients into a food processor and blitz in brief bursts until the mixture comes together in a soft paste.

- Tip the mixture out onto a piece of parchment and knead in the chopped walnuts.

- Lay clingfilm over the dough and roll it out thinly (5mm).

- Slide the sheet of covered dough onto a chopping board and freeze for 20 minutes. The dough is very soft and chilling it hard will make cutting the biscuits out and transferring them to the baking sheet much easier and with no loss of shape.

- Turn the oven to 160°C, 140°C Fan.

- Cut the dough into biscuits using a plain 5cm round cutter. Lay the biscuits on a baking sheet covered with baking parchment. There’s little to no spreading during baking, so you can lay them as close as 1cm from each other.

- Poke holes in the centre of your biscuits using a cocktails stick. Or not. I tried both ways, and to be honest, there wasn’t really a difference. Arguably the biscuits with the perforations, as in the photo at the top, maybe look a little more aesthetically pleasing, but not by much. You choose.

- Bake for 30 minutes, turning the baking sheet around halfway through to ensure even baking.

- Remove from the oven and allow to cool on the tins. The biscuits are rather friable when warm, so don’t be too eager to move them.

- Store in an airtight container when cold.

Blue Cheese Filling/Dip

150g (1 pack) Saint Agur blue cheese

280g (1 large box) Philadelphia cream cheese

- Remove both ingredients from the fridge and allow to come to room temperature.

- Crumble the blue cheese into a bowl and mash with a fork or the back of a spoon until smooth.

- Add half the cream cheese and mix thoroughly, making sure there are no lumps.

- Add the rest of the cream cheese and mix until smooth and fully incorporated.

- Fill a piping bag fitted with a 5mm star nozzle, and pipe onto half your biscuits.

- Top with the remaining biscuits and arrange on a serving plate.

- Use any remaining filling as a dip by adding a little cream/creme fraiche, yogurt until the desired consistency is reached.