The Lancashire Butter Pie is a regional, traditional pie specific to western Lancashire, especially the area around Preston, and has also been known as Friday Pie and Catholic Pie.

Preston has traditionally had a strong Catholic presence. In Tudor times, it was resistant – and at times downright hostile – to the Reformation. In 1583 the bishop of Chester denounced it as having a people ‘most obstinate and contemptuous’ of the Elizabethan laws on religion.

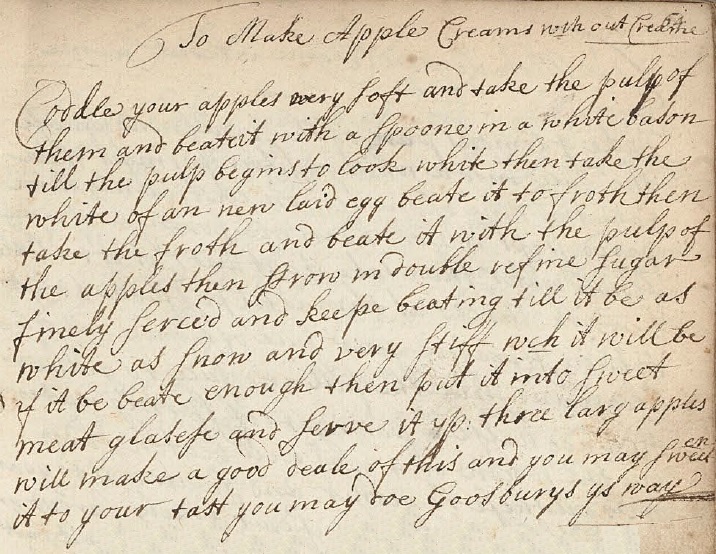

Since it was forbidden for Catholics to eat meat on Fridays, this pie, having only three simple ingredients, was ideally suited to the pious abstaining from their usual rich fare. And it does make for a good ‘story’.

However, my curiosity over the fact that it is the butter that gives the dish its name, rather than the potatoes and the onions led me to do some digging around into the pie’s history. My thoughts were that, although butter is commonplace for us now, it must have been regarded as a delicious treat in poorer times.

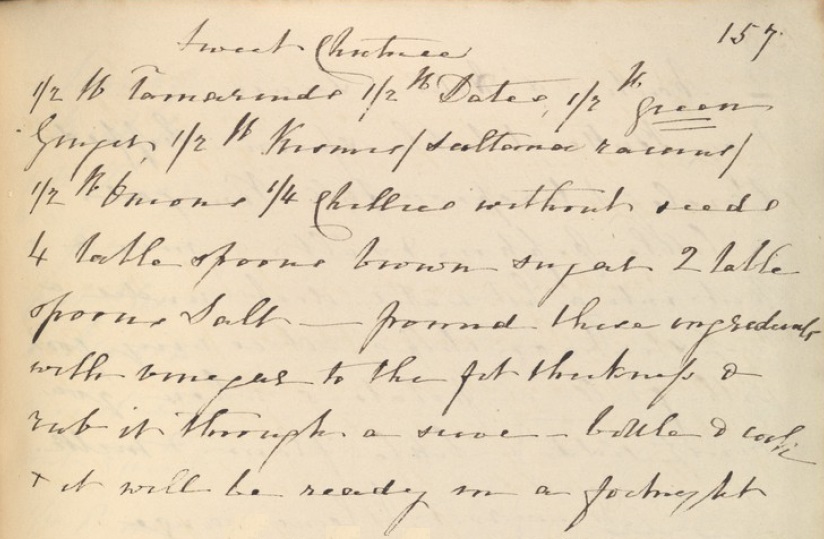

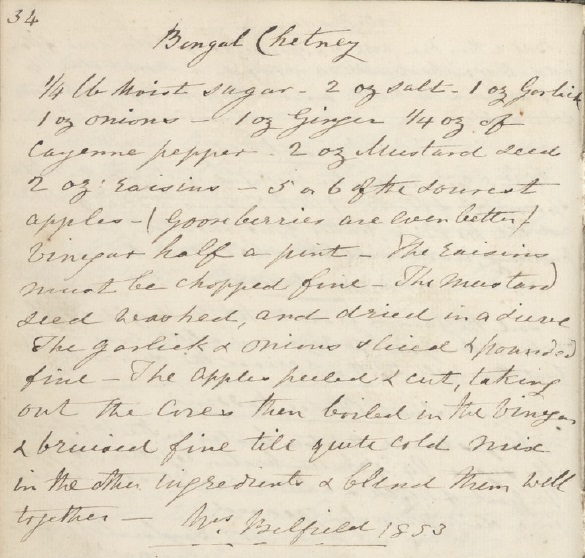

The modern incarnation of Butter Pie is alleged to owe much to the British Butter board, although I can find no verification for this. What I did find was what could be an ancestor of the modern recipe, in an account of the desperately poor existence of the cotton weavers of Lancashire, dating from 1827.

Joseph Greenwood, a worthy man of independent spirit, who has never troubled his parish, 60 years of age, with a wife and six children, lives at Bridge Inn, two miles and a half from Todmorden, on the Burnley road. He has five looms, and has wound and wove in his family, on an average, every week for the last four weeks, 16 pieces, each 30 yards of super calico, 28 west, at 9d, which gets 12s. per week. This sum is to support eight persons, pay rent, fire, clothes, candles to work by, shuttles, repair looms, &c. yet he will not run into debt. This family’s mode of living is as follows: they purchase a quantity of oatmeal, make gruel of oatmeal, salt, and water only, which serves for breakfast and supper; for dinner they bake a small quantity of the meal into a cake, and buy a little blue milk, as they call it, at ½d. per quart, and sup the milk along with the cake, but this is a luxury they cannot have every day. By way of change they sometimes buy wheaten flour to make the porridge, but with that they cannot afford to have the milk. Butter, cheese, and flesh meat, weavers never think of, unless now and then they purchase two ounces or a quarter of a pound of butter: or one or two pennyworth of suet, or odd bits of interior meat, to make a potatoe pie. The mode of making this pie is as follows: the potatoes are washed and cut into, slices, placed in a dish and sprinkled with salt, then filled up with water, the bits of suet are mixed with the potatoes, and the whole is covered with a thin crust, and if they cannot raise the suet or butter, the pie is made without them.[1]

Porridge morning and evening, oatcakes and skimmed milk for lunch. Having to choose between skimmed milk or wheat flour. Potato Pie as a treat. It’s a sobering thought. And little wonder that the tale of it being a dish of abstinence is the more popular, or at least, easier on the conscience. In this modern age, we are sometimes a bit too blasé about food and shameless with food waste. The story behind Butter Pie makes me, at least, be grateful for the abundance we have. This pie was a treat. IS a treat. No matter the humble ingredients.

So, if I haven’t plunged you irretrievably into a pit of despair, let’s talk ingredients!

This pie is deliciously savoury and ‘toothsome’ as Victorians were wont to say – ridiculously so, given the simplicity of its ingredients. Even with such a short list, you can vary the mix to produce delicately nuanced and finely-tuned combinations whilst still respecting the original.

My absolute favourite potato is the Pink Fir Apple, a fingerling-type potato with such a delicious flavour, I eat them as they are – no butter, no salt – they’re that good. In terms of texture, they sit perfectly between floury and waxy, relieving me of having to choose between these two different types of tuber. They aren’t very easy to find, alas. Many people have a specific preference, and will deign to eat only that one type. I, however, believe that there are times when one is more suited to a recipe than the other, and in this recipe you can celebrate both types according to the season. In spring and summer, use waxy new potatoes and spring onions or chives for freshness. In autumn and winter, big slices of soft, floury King Edward or Wilja potatoes with delicately softened brown onions turn this into an unctuous and comforting dish.

Whichever style you choose, the pastry should provide contrast against which the filling can really shine. Now you could be forgiven for thinking that with such a buttery filling, a rich buttery puff pastry would be the way to go, and you would be perfectly within your rights to try it, but it would not be the best option. It’s just too rich. Everything gets lost. My recommendation is for a cornflour, all butter, shortcrust pastry. It bakes incredibly crisp and the presence of the cornflour makes it a dry crispness – something not usually achievable with an all-butter pastry. And this unassuming, plain pastry is the perfect background for the soft, buttery filling to shine. It’s all about contrasts, of textures as well as flavours. You need the plainness of the pastry to really enjoy the rich-tasting filling.

Lancashire Butter Pie

The choice of potato is entirely up to you. I used Anya potatoes this time. The quantity of butter in the filling is restrained: you can also dot more over the potato layers if you’re feeling indulgent.

Pastry

225g plain flour

60g cornflour

140g unsalted butter

ice cold water

- Put the flours and butter into the bowl of a food processor and blitz until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs.

- With the machine running, gradually add the cold water a tablespoon at a time until the mixture comes together in a ball.

- Tip the mixture onto a floured surface, knead smooth then wrap in clingfilm and chill for 30 minutes.

- Remove the pastry from the fridge and cut off two thirds. Put the remaining third back into the fridge.

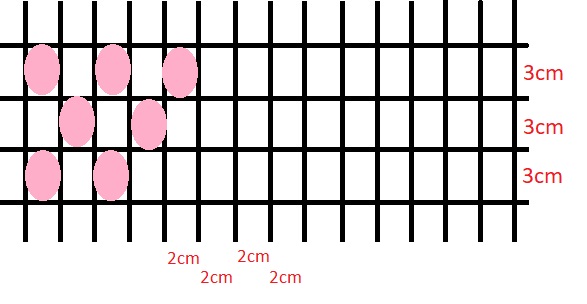

- Roll this piece out to a thickness of 4-5mm and use it to line a greased 18cm pie tin, loose-bottomed for preference, making sure there is enough pastry overlapping the sides of the tin to allow for joining the lid.

- Chill the pastry while you prepare the filling.

Filling

750g potatoes

120g unsalted butter

2 medium onions

salt and ground white pepper

1 egg yolk for glazing

- Peel the potatoes and cut into 1cm slices.

- Boil or steam (preferred) until tender. Spread out on a clean cloth to cool/dry.

- Chop the onions finely.

- Melt the butter in a pan and add the onions.

- Cook gently over a low heat until softened. Do not allow them to take any colour.

- Spread a thin layer of buttery onions over the base of the pastry and season with pepper and salt. Cover with a layer of potato slices, cutting them if necessary to fill any gaps.

- Repeat until the pie is filled, remembering to season each layer of onions. Pour any remaining butter over the top.

- Roll out the remaining pastry to make a lid.

- Damp the edges of the pastry and lay the lid on top. Trim to leave a border of 1cm.

- Crimp the pastry edges between finger and thumb. Gently press the crimped edge inwards until it is standing vertical.

- Mix the yolk with 1-2tsp cold water, and glaze the pastry lid thoroughly using a brush.

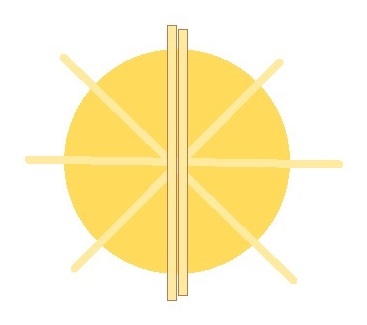

- Cut out some decorations from the offcuts of pastry and arrange on top of the glaze. Leaving the decorations unglazed will keep them from taking on too much colour in the oven, which means they will stand out more when baked. Cut a steam vent in the centre of the lid.

- Chill the pie in the fridge while the oven heats up.

- Heat the oven to 200°C, 180°C Fan.

- Bake the pie for 40-45 minutes, turning it around after 20 minutes to ensure even browning.

- Allow to cool for at least 10 minutes before turning out and serving.

- Also delicious cold.

[1] Niles’ National Register, Volume 32, 1827, p118

Trim the pastry ends neatly.

Trim the pastry ends neatly. Return the pastries to the fridge and chill until firm. When thoroughly chilled, transfer each tart to a separate piece of parchment paper. using a sharp knife, cut down between the two vertical strips of pastry, and draw each half apart.

Return the pastries to the fridge and chill until firm. When thoroughly chilled, transfer each tart to a separate piece of parchment paper. using a sharp knife, cut down between the two vertical strips of pastry, and draw each half apart. Heat the oven to 205°C/185°C Fan. Brush all the puff pastry edges with egg glaze and bake them until puffed and golden brown, 25-30 minutes. Cool on a wire rack.

Heat the oven to 205°C/185°C Fan. Brush all the puff pastry edges with egg glaze and bake them until puffed and golden brown, 25-30 minutes. Cool on a wire rack.