If you’d asked me only a few years ago, of my opinion of gingerbread, I would have given an indifferent shrug in response: I didn’t dislike it, but I wasn’t a fervent fan either. Ginger biscuits and the gingerbread used for gingerbread men I thought dull. Ginger cake was fine, but it would never be a first choice. Since then, I have discovered so many old recipes that have range and depth and nuance that it’s turned my head completely. And here we have another to add to the collection.

Ormskirk Gingerbread has a lot going for it, and I’d even go so far as to say it is probably one of the best-tasting gingerbreads you’ve never heard of.

It has a speckled appearance, from mixing the dry ingredients with melted butter and treacle, which is enough to bind, but not drown. There is candied peel, traditionally lemon but sometimes others, and spices, usually ginger, but frequently, additional spices as well. A major attraction, for me at least, is the texture, falling between the softness of parkin and the crispness of a biscuit. As you, quite literally, sink your teeth into a piece, you experience a dense chewiness which, with the variety of flavourings, is immensely satisfying.

Ormskirk Gingerbread (1830s) is one of the earliest geographically-linked gingerbreads I’ve found – predated only by Wrexham Gingerbread (1828). In the 1850s, a group of five local women paid £20 per year to the East Lancashire Railway company for the privilege to sell their gingerbread to travellers passing through Ormskirk station, which must have contributed to the spread of its popularity.

I have a selection of recipes for you to try, because in all honesty, I like them all. The method is the same for all of them, so I shall be listing the scaled-down ingredients alongside each recipe, then you can scroll down to the method and cooking instructions. All quantities are for a 20cm square tin.

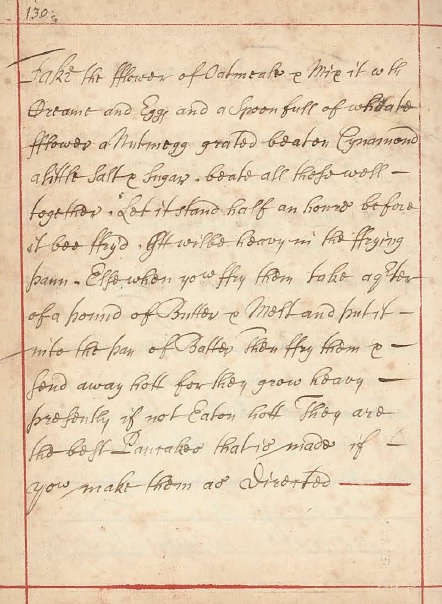

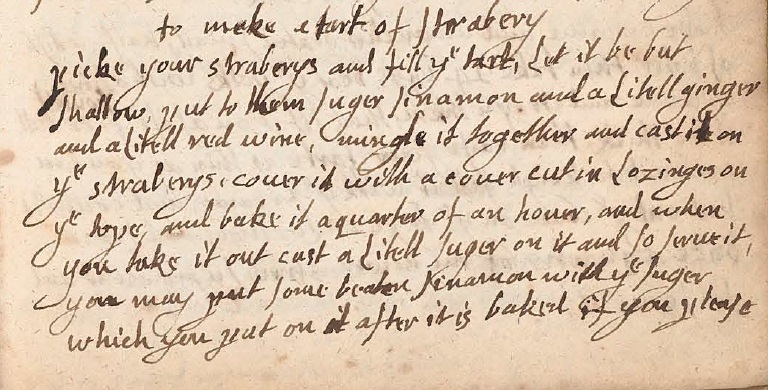

This recipe is from a handwritten manuscript held at the Wellcome Collection. It might actually be older than the recipe below, but there’s no way of telling for sure. Rather unhelpfully, there are no instructions for either making or baking, but it clearly contains all the classic ingredients and is a great introduction to this type of gingerbread:

225g plain flour

115g soft, light brown sugar

7g/1tbsp ground ginger

85g butter

115g treacle

20g candied lemon peel

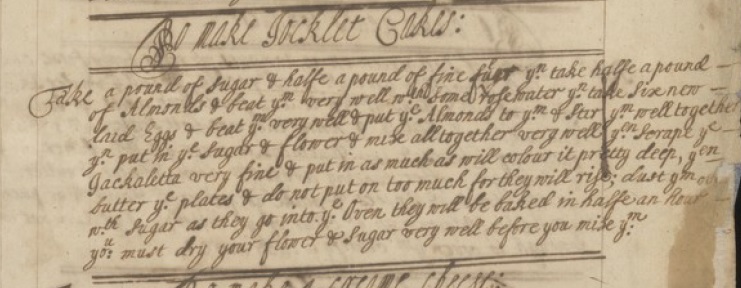

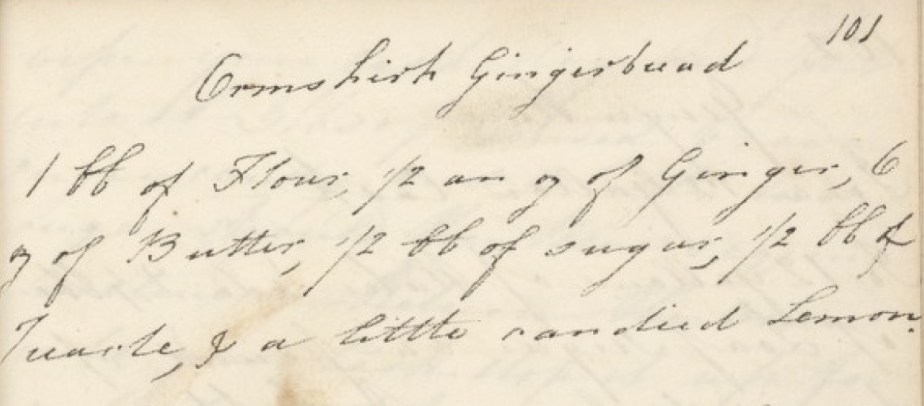

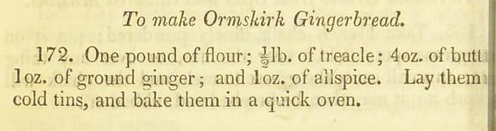

This is the earliest printed recipe I found. Unfortunately, it contains an error – the sugar is missing. Aside from this, what I found interesting was the complete omission of what appears to be a major component of other recipes, the candied lemon peel. In addition, there is, proportionally, a lot of spice in relation to the quantity of flour, but it is an interesting variation. In the past, I have bought dried, chipped ginger, and ground it as needed, and the flavour is bright and vibrant and, curiously, with a touch of lemon. Similarly with allspice, whose flavour really evokes a blend of spices.

225g plain flour

60g butter

115g treacle

115g soft, light brown sugar

14g ground ginger

14g allspice

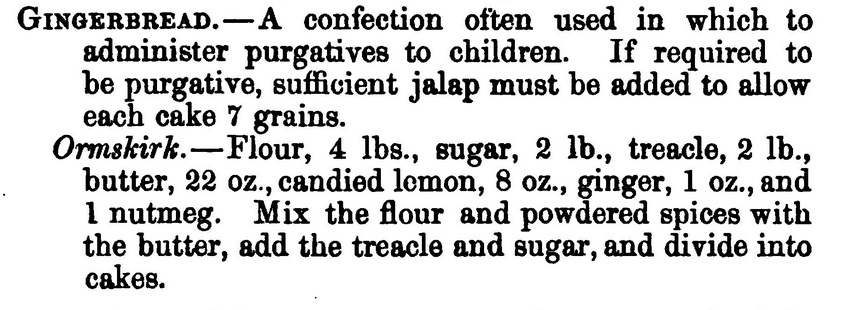

This recipe echoes the medicinal uses many believed gingerbread possessed in the middle ages. I find it odd that it is Ormskirk Gingerbread that is specified in particular, instead of a generic gingerbread recipe. Jalap is the ground root of a Mexican plant of the Morning Glory family, and it was used in times past for its laxative effect.

225g plain flour

115g soft, light brown sugar

115g treacle

80g butter

30g candied lemon peel

2 tsp ground ginger

1½ tsp ground nutmeg

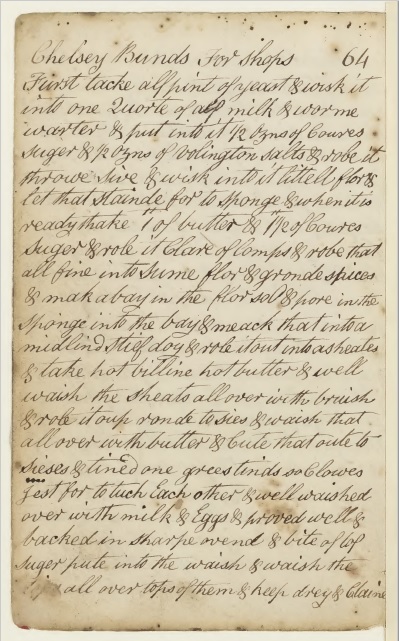

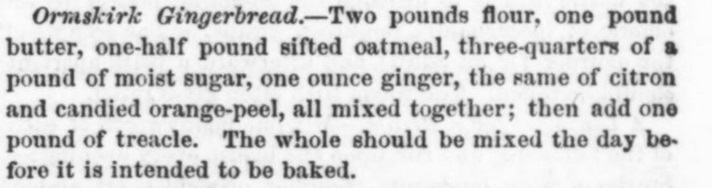

This last recipe is a full-on, all the bells and whistles version. There’s no candied lemon peel – instead there’s candied orange and candied citron and, aside from the ginger, no other spices. There’s a higher than usual farinaceous component, with the addition of some oatmeal flour (which you can make yourself by putting rolled oats into a blender/spice mill). Finally, there’s the instruction to mix it a full day before you want to bake it. Many old gingerbread recipes have this added time requirement, because they’d also use alum and potash as raising agents, and these worked slowly, so a mix for gingerbread could be sitting in a tub for days if not weeks. There’s no raising agent included in this recipe, so I was curious whether there would be any difference to the other batches. Verdict: There was, and the resulting gingerbread was definitely veering towards cakey, although this might have been due to the added oatmeal – if that’s your preferred texture, have at it. The next time I make this I probably wouldn’t wait the 24 hours, but that’s just me being impatient.

225g plain flour

115g butter

60g sifted oatmeal flour

80g soft, light brown sugar

115g treacle

15g candied orange peel

15g candied citron peel

7g ground ginger

As I said at the top, all these recipes are delicious.

Ormskirk Gingerbread

Another reason to choose to make this gingerbread is that it can be made gluten-free, using gluten-free flour (I used Doves Farm) and gluten-free oats (Morrisons have the nicest looking GF oats – they’re like steel-rolled ones!).

It can also be made vegan, if you swap out the butter for either coconut oil or some other fat that is solid at room temperature.

Finally, there’s two slight variations in method, and it relates to how you handle the butter. The traditional method for gingerbread is to melt it in the treacle and then pour the mixture into the dry ingredients to mix. The other method is to blitz it with the dry ingredients in a food processor (or rub it in by hand). It doesn’t matter which method you choose, as the result is the same.

- Choose your ingredients from one of the four recipes above.

- Line a 20cm square tin with baking parchment.

- Heat the oven to 160°C, 140°C Fan.

- Mix your spices, sugar and flour(s).

- If you’re blitzing the butter with the dried ingredients, add it now.

- Blitz the mixture to resemble breadcrumbs.

- Slice the candied peel thinly and then cut into 1cm pieces. Mix the peel into the dry ingredients, making sure the pieces don’t stick together.

- Pour your treacle into a pan to warm. I use a large frying pan, as I prefer to add everything to the treacle, as opposed to pouring the treacle into the dry ingredients. Add the butter if you’ve not added it to the flour. You’re not trying to boil it, just warm it up enough that it moves freely and the butter (if using) is melted.

- When the butter has melted and the treacle warmed, pour the warm liquid into the dry ingredients and mix in. It doesn’t have to be evenly coloured.

- Tip the mixture into your prepared pan and level out. I like to leave it rather roughly textured. Don’t press the mixture down hard, just even it out.

- Bake for 40 minutes, turning the tin around after 20 minutes to ensure even baking.

- Remove from the oven and , leaving the gingerbread in the tin, divide it into pieces. You can cut it into any shape you please – easiest with a square tin is 16 pieces (4 x 4 grid).

- Set the pan aside to cool completely.

- When the gingerbread is cold, store in an airtight container.